Guide to U.S. expat taxes in Spain

Living in Spain is a wonderful experience, combining modern cities, rich traditions, and delicious food. However, there are important responsibilities to manage, and taxes are a big part of that. As a U.S. citizen living in Spain, you need to handle taxes in both countries.

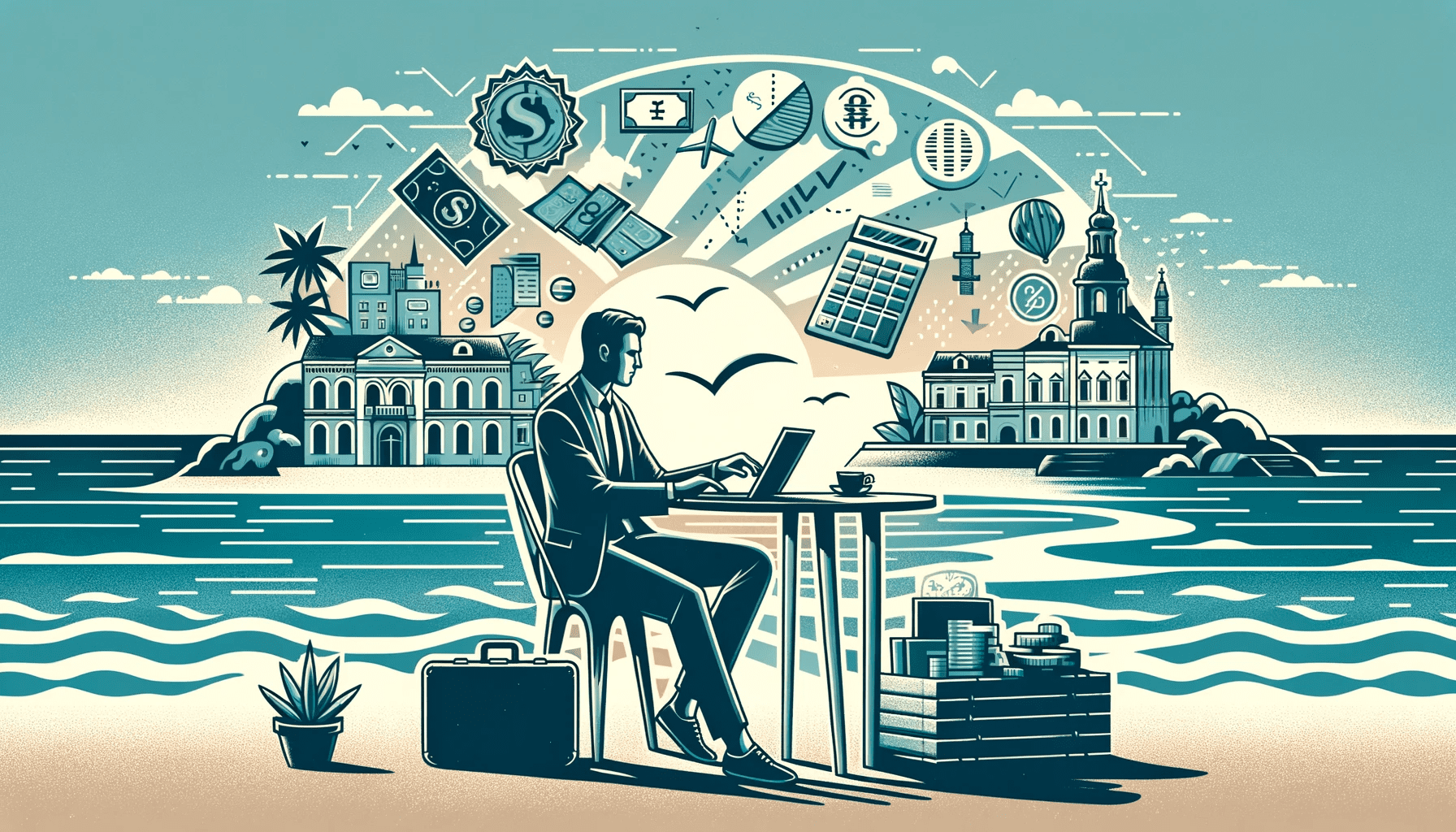

It is important to understand the Spanish tax system to manage your taxes effectively. The U.S. tax system is different because it taxes citizens no matter where they live. This means that even if you earn money in Spain, you still have to file a tax return with the IRS. Spain also has its own tax rules for residents and foreigners. While this may seem complicated, there are ways to avoid paying taxes in both countries.

U.S. federal tax obligations for expats

Living in Spain doesn’t mean you can ignore U.S. taxes. The U.S. is one of the few countries that taxes its citizens no matter where they live. But don’t worry—it’s not as bad as it sounds, and many expats end up owing little or nothing. Let’s break it down:

Tax treaties between the U.S. and Spain can help mitigate the risk of double taxation and provide clarity on tax obligations.

The U.S. tax system mandates that citizens and resident aliens report all income from global sources. This includes:

- Employment Income: Salaries, wages, bonuses, and commissions earned in Spain or any other country.

- Self-Employment Income: Earnings from freelance work or business operations conducted abroad.

- Investment Income: Interest, dividends, capital gains, and rental income from both U.S. and foreign sources.

Regardless of where the income is earned or where you reside, it must be reported to the Internal Revenue Service (IRS).

Example: If you earn €40,000 working in Spain, that income must be reported on your U.S. tax return, even if you already paid taxes on it in Spain.

Filing requirements and thresholds

The requirement to file a U.S. tax return and pay income tax depends on your filing status, age, and gross income. For the tax year 2024, the thresholds are as follows:

- Single Filers: Must file if gross income is at least $13,850.

- Married Filing Jointly: Must file if combined gross income is at least $27,700.

- Married Filing Separately: Must file if gross income is at least $5.

- Head of Household: Must file if gross income is at least $20,800.

These thresholds are subject to annual adjustments for inflation. It’s crucial to verify the current year’s thresholds to ensure compliance.

Key tax exclusions and credits

Paying taxes in both Spain and the U.S. might sound like a headache, but luckily, there are ways to avoid double taxation.

As a U.S. expat, you are required to pay taxes on your income, but there are mechanisms to reduce your overall tax burden. The U.S. offers expats several tools to reduce or eliminate their tax liability, so you don’t have to pay twice on the same income.

Foreign Earned Income Exclusion (FEIE)

The FEIE allows qualifying U.S. expats to exclude a certain amount of foreign-earned income from U.S. taxation. For 2023, this exclusion amount is up to $126,500.

To qualify, you must meet one of the following tests:

- Physical Presence Test: You’ve spent at least 330 full days in Spain (or another foreign country) during any 12-month period.

- Bona Fide Residence Test: You’ve spent at least 330 full days in Spain (or another foreign country) during any 12-month period.

To claim the FEIE, file Form 2555 with your U.S. tax return.

Example: If you earn $80,000 working in Spain, you can exclude the entire amount using the FEIE, leaving you with no U.S. taxes owed on that income.

Foreign Tax Credit (FTC)

The FTC allows you to offset your U.S. tax liability with the taxes you’ve paid to Spain. This credit works dollar-for-dollar, which is especially useful if Spain’s taxes are higher than U.S. taxes.

Example: If you owe $10,000 in Spanish taxes and $8,000 in U.S. taxes, the FTC can cancel out your U.S. tax bill entirely.

Foreign Housing Exclusion

Spain has some of the best housing options in Europe, and you can use the Foreign Housing Exclusion to deduct certain housing costs from your U.S. taxable income.

Example: If your rent in Madrid is $2,000/month, a portion of this expense can be excluded from your U.S. taxable income, further lowering your tax bill.

State tax obligations for the U.S. expats in Spain

Federal taxes are only part of the story. If you lived in the U.S. before moving to Spain, you might still owe state taxes—depending on where you lived and whether you’ve formally severed ties with that state.

Determining state domicile

State tax obligations depend on whether your previous state of residence considers you a tax resident. Generally, your state of domicile—your permanent home—determines whether you owe state taxes. If you’ve moved to Spain but still maintain strong ties to your former state, such as owning property or holding a driver’s license, you may still be considered a tax resident.

To avoid ongoing state tax obligations, it’s often necessary to formally sever ties with your previous state of residence.

Here’s a breakdown of states by tax treatment:

States with no tax on worldwide income for non-residents

These states provide favorable tax treatment for expats, as they do not impose taxes on global income if you can establish non-resident status:

- Colorado

- Connecticut

- Delaware

- Massachusetts

- Minnesota

- Missouri

- North Dakota

- Oregon

- Pennsylvania

- Virginia

- West Virginia

Expats from these states may not need to take significant steps to maintain their non-resident status once they relocate. This group of states offers considerable savings by not taxing worldwide income, making them favorable options for expats.

States that tax worldwide income but offer FEIE

These states tax worldwide income but provide some relief to expats by allowing a Foreign Earned Income Exclusion (FEIE). For the 2024 tax year, the FEIE lets expats exclude up to $126,500 of foreign-earned income from state income tax.

- Alabama

- Arizona

- Georgia

- Idaho

- Illinois

- Indiana

- Iowa

- Kansas

- Kentucky

- Maine

- Michigan

- Ohio

- Oklahoma

- Rhode Island

- South Carolina

- Utah

- Vermont

While these states tax global income, expats can reduce their tax liability with the FEIE, which allows them to exclude a significant portion of their foreign earnings.

States that tax worldwide income with no FEIE

These states tax worldwide income but do not provide a Foreign Earned Income Exclusion, resulting in higher potential tax burdens for expats, as there is no mechanism to offset foreign-earned income:

- Arkansas

- Indiana

- Kentucky

- Louisiana

- Maine

- Maryland

- Mississippi

- Montana

- Nebraska

- New Mexico

- North Carolina

- Wisconsin

Expats domiciled in these states face more significant tax liabilities on their global income due to the lack of FEIE, which makes establishing domicile elsewhere more appealing.

States with the highest tax burden for expats

Some states impose the most stringent tax policies on expats, including high income tax rates and no exclusions for foreign-earned income. If you’re domiciled in one of these states, relocating your domicile to a more tax-friendly state can lead to substantial savings.

These states have high income tax rates and tax worldwide income with no exclusions, making them the least favorable for expats in terms of tax savings.

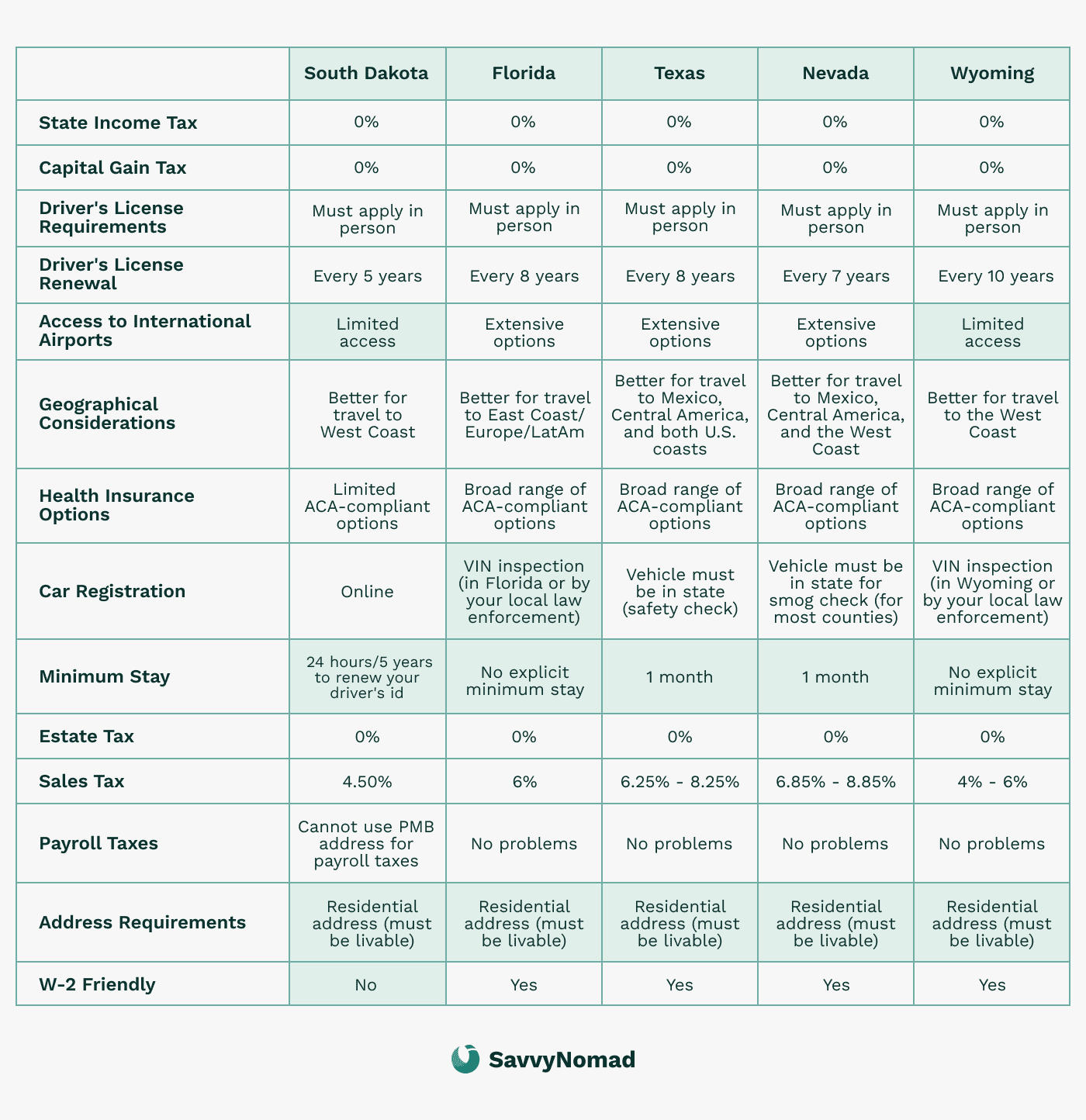

Steps to reduce state tax obligations

If you plan to avoid state tax obligations, especially from states that tax worldwide income without providing relief, consider these steps:

- Establish domicile in a tax-friendly state: Moving your official residence to a state with no income tax, like Florida, Nevada, Texas, or South Dakota, can significantly reduce your tax burden.

- Update official documents: Cancel voter registration, update your driver’s license, and transfer financial accounts to reflect your new domicile.

- File a final tax return in your previous state: This signals the end of your tax residency and helps prevent future state tax liabilities.

Additional U.S. reporting requirements – FATCA and FBAR

Living abroad comes with extra responsibilities, especially when it comes to reporting foreign accounts and assets. The U.S. government requires you to file additional forms to track overseas financial activity. While it might feel like more paperwork, staying compliant will save you from hefty penalties.

FATCA (Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act)

The Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act, or FATCA, was introduced to help the IRS prevent tax evasion by U.S. citizens using foreign accounts. FATCA requires U.S. taxpayers to report certain foreign assets to the IRS. Here’s what you need to know about FATCA and its requirements:

Who needs to file under FATCA?

If you have foreign assets that exceed certain thresholds, you’ll need to report them on Form 8938, which is submitted along with your regular tax return. For single filers living abroad, the threshold is $200,000 on the last day of the tax year or $300,000 at any point during the year. For married couples filing jointly, the thresholds are doubled.

What needs to be reported?

Reportable assets under FATCA include foreign bank accounts, investment accounts, foreign stocks, and even certain pensions. Generally, any financial assets held outside the U.S. should be reviewed to determine if they need to be reported.

How to file FATCA (Form 8938)?

FATCA, or the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act, is a U.S. law that requires U.S. citizens to report certain foreign financial assets to the IRS. As a U.S. expat living in Spain, you may be required to file Form 8938, which is the form used to report these assets.

Here’s how to file:

- Determine if You Need to File: You’ll need to file Form 8938 if you have foreign financial assets with an aggregate value of $50,000 or more on the last day of the tax year or $75,000 or more at any time during the tax year.

- Gather Required Information: You’ll need to gather information about your foreign financial assets, including the name and address of the financial institution, the account number, and the value of the assets.

- File Form 8938: You’ll need to file Form 8938 with your tax return (Form 1040). You can file electronically or by mail.

Staying compliant with FATCA requirements helps avoid hefty penalties and ensures that your foreign financial assets are properly reported.

FBAR (Foreign Bank Account Report)

The Foreign Bank Account Report (FBAR) is another requirement for U.S. citizens with overseas accounts. While FATCA applies based on the value of financial assets, the FBAR requirement is specifically tied to foreign bank accounts. Here’s a breakdown:

Who needs to file FBAR?

If the combined balance of all your foreign bank accounts exceeds $10,000 at any point during the year, you’re required to file an FBAR. This rule applies even if you just temporarily crossed the $10,000 threshold. For instance, if you have two accounts—one with $5,000 and another with $6,000—you would need to file an FBAR, as the combined balance is over $10,000.

Example: If you have a Spanish bank account with €5,000 and a savings account with €6,000, their combined value exceeds $10,000, so you must file an FBAR.

How to file the FBAR (fincen form 114)?

The FBAR is filed separately from your tax return and is submitted online through the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN). The form, FinCEN Form 114, requires you to report details about each foreign account, including the bank name, account number, and maximum balance during the year.

Important deadlines and penalties

The FBAR filing deadline is April 15, but there is an automatic extension until October 15 for those who miss the initial deadline. Be mindful of FBAR filing, as the penalties for not reporting eligible accounts can be severe, with fines starting at $10,000 for each unreported account.

Understanding the difference between FATCA and FBAR

While FATCA and FBAR both aim to provide the IRS with information about foreign financial accounts, they have distinct differences:

- Different thresholds: FATCA requires reporting if your foreign assets exceed $200,000 as a single filer, while FBAR applies if the total balance in all foreign accounts exceeds $10,000.

- Different filing locations: FATCA reporting (Form 8938) is filed with your federal tax return, whereas the FBAR is filed separately through FinCEN.

- Types of assets reported: FATCA requires reporting a broader range of foreign financial assets, while FBAR focuses only on foreign bank accounts.

Why do FATCA and FBAR matter for U.S. expats?

Failing to file FATCA and FBAR can result in significant penalties, so it’s essential to understand whether you’re required to report these assets. While it may seem like an extra step, filing these forms can help ensure compliance with IRS regulations and avoid unnecessary fines.

If you have foreign bank accounts or financial assets, it’s a good idea to consult a tax professional to ensure you’re meeting all reporting requirements.

Spain tax obligations for U.S. expats

If you’re living in Spain as a U.S. expat, understanding Spain’s tax system is critical to staying compliant and avoiding unnecessary penalties. Personal income taxes in Spain are progressive, with rates varying based on your income level and region.

Spain taxes its residents on their worldwide income, but there are unique opportunities, like the Beckham Law, that can make a big difference in your tax obligations.

Determining tax residency in Spain

Spain considers you a tax resident if you meet any of these criteria:

- Family Residency: Your spouse or dependent children reside in Spain.

- Economic Ties: Your primary income sources or economic interests are in Spain.

- 183-Day Rule: You spend 183 days or more in Spain during a calendar year.

Tax residents in Spain are required to report their worldwide income and comply with local tax laws.

As a tax resident, you must report worldwide income, including earnings from the U.S. and other countries. You’ll only be taxed on income sourced in Spain if you’re a non-resident.

Spanish income tax rates

Spain uses a progressive tax system, with rates varying slightly by region. For 2024, the general national brackets are:

- Up to €12,450: 19%

- €12,451 to €20,200: 24%

- €20,201 to €35,200: 30%

- €35,201 to €60,000: 37%

- Over €60,000: 45%

In addition to income tax, Spain also imposes a capital gains tax on profits from selling property or other investments.

Regions like Catalonia and Andalusia may impose additional taxes, so your total rate could be higher depending on where you live.

Local Inhabitant Taxes

In addition to national income taxes, Spain imposes local taxes, typically around 1%–2% of your taxable income. These are collected by your local municipality.

The Beckham Law

Spain offers a special tax regime for certain expats called the Beckham Law (Royal Decree 687/2005). Designed to attract foreign talent, it provides favorable tax conditions for qualifying individuals.

- Flat tax rate of 24% on income up to €600,000 (compared to progressive rates for residents).

- Non-resident treatment for worldwide income, meaning only Spanish-sourced income is taxed.

- Capital gains and wealth tax are limited to assets in Spain.

- No requirement to file the Modelo 720, which declares assets held abroad.

Eligibility Criteria:

- You must not have been a tax resident in Spain for the past five years.

- Your move to Spain must be related to employment, entrepreneurial activity, or becoming an administrator of a Spanish company.

- You must apply within six months of starting your job in Spain.

Example: If you earn €300,000 annually, the Beckham Law allows you to pay a flat 24% rate instead of up to 45%, saving significant taxes.

Wealth Tax

If your worldwide net assets exceed €700,000, you may be subject to Spain’s wealth tax. Rates range from 0.2% to 3.5%, but under the Beckham Law, only Spanish assets are taxed.

Inheritance tax in Spain

Inheritance tax in Spain is a complex topic, and the rules vary depending on the region. Here’s a general overview:

- Tax Rates: Inheritance tax rates in Spain range from 7.65% to 34%, depending on the region and the value of the inheritance.

- Exemptions: There are exemptions for inheritances between spouses, parents, and children, as well as for inheritances of up to €15,000.

- Tax-Free Allowance: There is a tax-free allowance of €700,000 for inheritances of up to €10 million.

Understanding these rules can help you plan your estate and minimize the tax burden on your heirs.

Property tax in Spain

Property tax in Spain is a municipal tax that’s levied on the ownership of property. Here’s a general overview:

- Tax Rates: Property tax rates in Spain vary depending on the municipality and the type of property.

- Exemptions: There are exemptions for certain types of property, such as primary residences and properties owned by non-residents.

- Tax-Free Allowance: There is a tax-free allowance of €300,000 for primary residences.

Being aware of these taxes and exemptions can help you manage your property-related expenses more effectively.

Tax deductions and allowances in Spain

As a tax resident in Spain, you may be eligible for various tax deductions and allowances.

Here are some of the most common:

- Employment Expenses: You can deduct employment-related expenses, such as transportation costs, meals, and professional fees.

- Business Expenses: If you’re self-employed, you can deduct business-related expenses, such as rent, utilities, and equipment.

- Rental Income: If you own a rental property in Spain, you can deduct mortgage interest, property taxes, and maintenance costs.

- Charitable Donations: You can deduct charitable donations to qualified organizations.

These deductions can significantly reduce your taxable income, making it essential to keep detailed records of all eligible expenses.

Filing deadlines and tax year in Spain

- Tax Year and Deadlines:

- Spain’s tax year runs from January 1 to December 31.

- The filing deadline is usually June 30 of the following year.

- Required Documents:

- Income statements (e.g., from your Spanish employer).

- Records of investment income or capital gains.

- Proof of deductible expenses like health insurance or charitable donations.

- How to File:

- Online through Spain’s Agencia Tributaria website.

- With the help of a tax professional familiar with expat taxes.

U.S.- Spain tax treaty

The U.S.-Spain Tax Treaty is a valuable tool for U.S. expats living in Spain. It’s designed to prevent double taxation, clarify which country taxes specific types of income, and provide mechanisms to reduce your overall tax burden.

Navigating both the U.S. and Spanish tax systems can be complex, but the tax treaty helps clarify your obligations. Understanding and using this treaty can make managing taxes much easier.

Purpose of the U.S.-Spain tax treaty

The main objectives of the tax treaty are to:

- Prevent Double Taxation: Ensure you aren’t taxed on the same income by both countries.

- Define Tax Rights: Establish clear rules on which country has taxing authority over specific types of income.

- Social Security Coordination: The treaty includes a Totalization Agreement to avoid paying into both the U.S. and Spainese social security systems.

By using the treaty, you can align your U.S. and Spainn tax filings to avoid paying more than you owe.

For U.S. expats, the treaty helps lower the risk of double taxation by allowing foreign tax credits, setting reduced tax rates on specific income types, and establishing residency and income allocation rules.

Key treaty provisions

- If you work in Spain, your salary is primarily taxed in Spain.

- You still report this income on your U.S. tax return, but you can use the Foreign Tax Credit (FTC) or Foreign Earned Income Exclusion (FEIE) to avoid U.S. taxes.

- Dividends and Interest:

- Dividends from Spanish investments are taxed in Spain, but the treaty caps the rate at 10%.

- Interest income is typically taxed only in your country of residence.

- Capital Gains: Capital gains from selling assets, like stocks, are generally taxed in your country of residence. If you’re a resident of Spain, Spain gets the taxing rights.

- Pensions and Retirement Income: Most pensions are taxed in your country of residence. For example, U.S.-based retirement income is usually taxed in Spain if you’re a Spanish resident, with some exceptions.

Employment Income:

Social Security Agreement (Totalization Agreement)

The Totalization Agreement simplifies social security contributions for expats:

- Avoid Double Contributions: If you’re working in Spain for a U.S.-based employer, you may remain in the U.S. Social Security system and avoid paying into Spain’s system.

- Combine Credits: Contributions in both countries can be combined to qualify for benefits.

- Receive Benefits Internationally: You can receive U.S. Social Security payments while living in Spain, and vice versa.

Example: If you worked in the U.S. for 6 years and in Spain for 5 years, the agreement allows you to combine these 11 years to qualify for U.S. benefits.

Key benefits

- Avoid Double Contributions:

- If you’re in Spain temporarily (5 years or less) working for a U.S.-based employer, you stay in the U.S. Social Security system and avoid Spain’s contributions.

- Spainese citizens in the U.S. get similar treatment.

- Combine Credits: Contributions in both countries can be combined to meet eligibility requirements for benefits in either system.

- Access Benefits Internationally: You can receive social security benefits from one country even while living in the other.

Claiming treaty benefits

To take advantage of the tax treaty, U.S. expats may need to file specific forms with the IRS:

- Form 8833 (Treaty-Based Return Position Disclosure): This form is required if you’re claiming treaty benefits to reduce or eliminate your U.S. tax liability on income earned in Spain.

- Form 1116 (Foreign Tax Credit): Use this form to claim credits for taxes paid to Spain on income also taxable by the U.S., helping to avoid double taxation.

Residency and tie-breaker rules

The treaty also includes “tie-breaker” rules to help determine tax residency if both countries consider you a resident. Here’s how the treaty resolves conflicts in residency status:

- Permanent Home: Priority is given to the country where you maintain a permanent home.

- Center of Vital Interests: If you have permanent homes in both countries, the country where you have stronger personal and economic ties (center of vital interests) takes precedence.

- Habitual Abode: If neither of the above determines residency, the country where you habitually reside is considered your primary tax residence.

These tie-breaker rules help avoid conflicts over tax residency and ensure that your tax obligations are clear.

Spain tax filing process for U.S. expats

If you’re a tax resident in Spain, you must report your worldwide income to the Spanish tax authorities. Here’s what you need to know:

Tax Year and Deadlines:

- Spain’s tax year runs from January 1 to December 31.

- The filing deadline is usually June 30 of the following year.

What You’ll Need to File:

- Income Records: Salary slips (from Spanish or foreign employers).

- Bank and Investment Statements: For dividends, interest, and capital gains.

- Proof of Deductions: Health insurance payments, pension contributions, or charitable donations.

How to File:

- Online: Through Spain’s Agencia Tributaria portal.

- In Person: At your local tax office, especially if you’re unfamiliar with the system.

- Hire a Tax Professional: Recommended for expats with complex finances or language barriers.

Key Deductions in Spain:

- Pension Contributions: To Spanish retirement accounts.

- Health Insurance Premiums: If not covered by an employer.

Education Expenses: For dependent children.