Guide to U.S. expat taxes in Brazil

Brazil is famous for its vibrant culture, stunning landscapes, and warm people. For U.S. expats, living in Brazil can be an adventure of a lifetime. But, as with any big move, there are responsibilities to manage—especially when it comes to taxes.

As a U.S. citizen, you’re required to report your worldwide income to the IRS, even if you’re living abroad. At the same time, Brazil has its own tax system, and you may need to pay taxes there too. Managing taxes in two countries might seem overwhelming, but don’t worry—this guide will break everything down into simple, manageable steps.

U.S. federal tax obligations for expats

Living in Brazil doesn’t mean you can ignore your U.S. tax responsibilities. The U.S. is one of the few countries that taxes its citizens no matter where they live. While this might sound like bad news, the reality isn’t as scary as it seems.

The U.S. tax system mandates that citizens and resident aliens report all income from global sources. This includes:

- Employment Income: Salaries, wages, bonuses, and commissions earned in Brazil or any other country.

- Self-Employment Income: Earnings from freelance work or business operations conducted abroad.

- Investment Income: Interest, dividends, capital gains, and rental income from both U.S. and foreign sources.

Regardless of where the income is earned or where you reside, it must be reported to the Internal Revenue Service (IRS).

Example: If you earn R$120,000 working in Brazil, that income must be reported to the IRS, even if you already paid taxes on it in Brazil.

Filing requirements and thresholds

The requirement to file a U.S. tax return depends on your filing status, age, and gross income. For the tax year 2024, the thresholds are as follows:

- Single Filers: Must file if gross income is at least $13,850.

- Married Filing Jointly: Must file if combined gross income is at least $27,700.

- Married Filing Separately: Must file if gross income is at least $5.

- Head of Household: Must file if gross income is at least $20,800.

These thresholds are subject to annual adjustments for inflation. It’s crucial to verify the current year’s thresholds to ensure compliance.

Key tax exclusions and credits

Paying taxes in both Brazil and the U.S.? That doesn’t sound fun. Luckily, there are tools and strategies in place to help you avoid double taxation. With the right approach, you can reduce or even eliminate your U.S. tax liability while staying compliant.

Foreign Earned Income Exclusion (FEIE)

The FEIE allows qualifying U.S. expats to exclude a certain amount of foreign earned income from U.S. taxation. Recent exclusion limits have been $120,000 for 2023, $126,500 for 2024, and $130,000 for 2025. The exact amount is indexed for inflation each year, so always check the current IRS limit when you file.

To qualify, you must meet one of the following tests:

- Physical Presence Test: You’ve spent at least 330 full days in Brazil (or another foreign country) during any 12-month period.

- Bona Fide Residence Test: You are a bona fide resident of a foreign country or countries for an uninterrupted period that includes a full tax year, based on your facts and circumstances.

To claim the FEIE, file Form 2555 with your U.S. tax return.

Example: If you earn $80,000 working in Brazil, you could use the FEIE to exclude the entire amount from U.S. taxes.

Foreign Tax Credit (FTC)

The FTC lets you reduce your U.S. taxes dollar-for-dollar for income taxes paid in Brazil. This is particularly useful because Brazil’s tax rates are often higher than U.S. rates.

Example: If you owe $10,000 in Brazilian taxes and $8,000 in U.S. taxes, the FTC can cancel out your U.S. tax bill entirely.

Foreign Housing Exclusion

If you’re living in Brazil, you can deduct certain housing expenses, like rent, from your U.S. taxable income. This exclusion is especially useful in higher-cost cities like São Paulo or Rio de Janeiro.

Example: If you pay $2,000 per month in rent, you can deduct a portion of that to further reduce your taxable income.

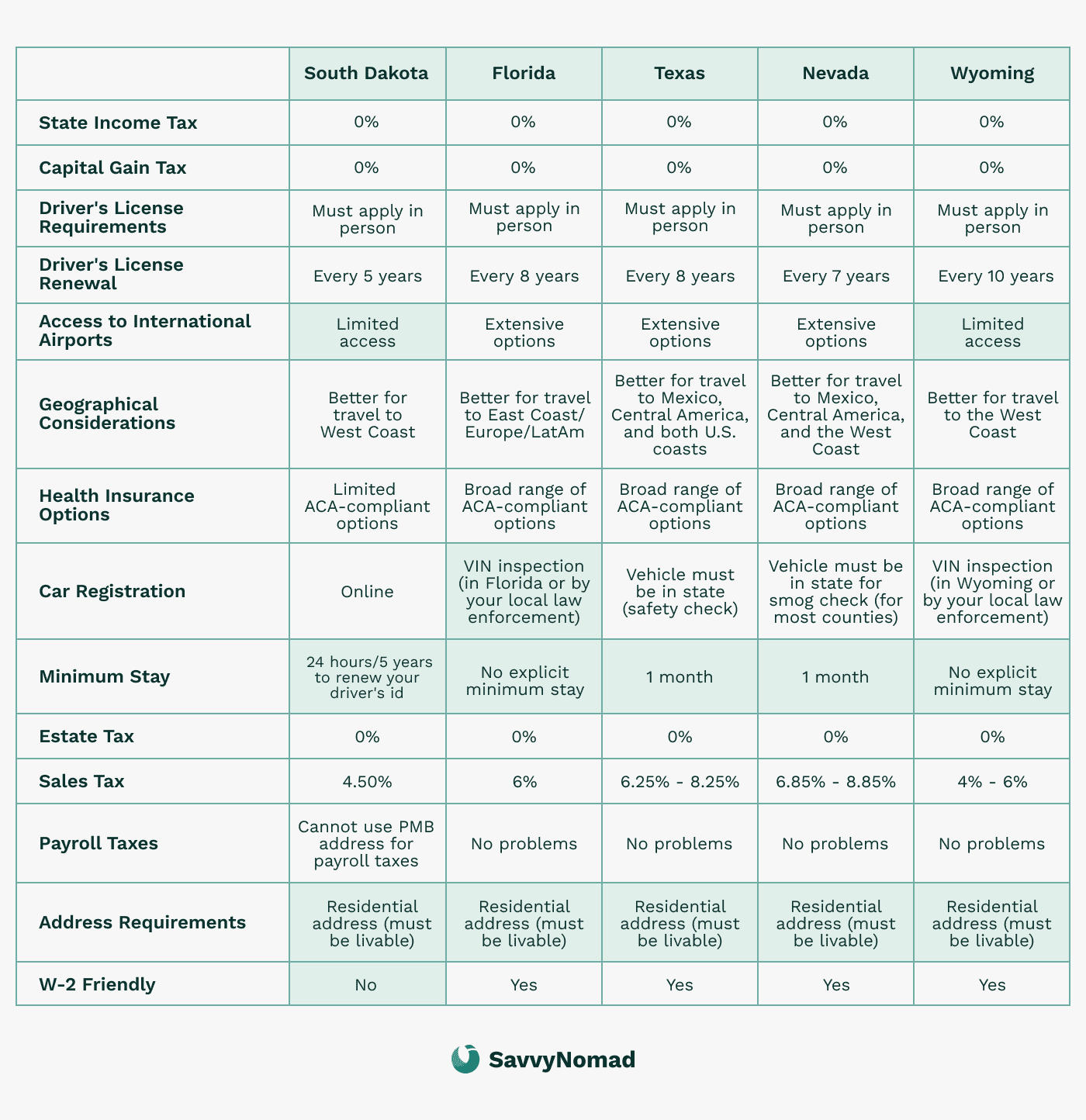

State tax obligations for the U.S. expats in Brazil

Federal taxes are just part of the picture. If you lived in the U.S. before moving to Brazil, you might still owe taxes to your former state—depending on where you lived and whether you’ve officially cut ties.

Determining state domicile

State tax obligations depend on whether your previous state of residence considers you a tax resident. Generally, your state of domicile—your permanent home—determines whether you owe state taxes. If you’ve moved to Brazil but still maintain strong ties to your former state, such as owning property or holding a driver’s license, you may still be considered a tax resident.

To avoid ongoing state tax obligations, it’s often necessary to formally sever ties with your previous state of residence.

Here’s a breakdown of states by tax treatment:

States with clear exit paths or no state income tax

These states are often the most favorable for expats because they either have no state personal income tax or have unusually clear and predictable nonresident rules. Once you have properly ended residency and domicile under their rules, they do not tax your worldwide income.

- Alaska

- Florida

- Nevada

- New Hampshire

- Ohio

- Pennsylvania

- South Dakota

- Tennessee

- Texas

- Washington

- Wyoming

States that tax worldwide income but offer FEIE

These states tax worldwide income for residents, but they generally begin from federal adjusted gross income, so the federal FEIE amount usually flows through to the state for qualifying residents.

For recent tax years, the FEIE limits have been $120,000 for 2023, $126,500 for 2024, and $130,000 for 2025 at the federal level. When a state starts from federal AGI and has not decoupled, your excluded income is typically not taxed again by that state.

States in this group include:

- Alabama

- Colorado

- Georgia

- Illinois

- Indiana

- Iowa

- Kansas

- Kentucky

- South Carolina

- Utah

While these states tax global income for residents, expats who qualify for FEIE can often reduce their state taxable income because the exclusion is already reflected in federal AGI. Residency rules and any specific state decoupling still control how each state treats your income.

While these states tax global income, expats can reduce their tax liability with the FEIE, which allows them to exclude a significant portion of their foreign earnings.

States that tax worldwide income with no state level FEIE

Many other states tax worldwide income for residents and do not allow the federal FEIE to directly reduce state taxable income. In those states, expats who remain domiciled there can be taxed on their global income with no state level exclusion for foreign earned income.

Examples include states such as California, Hawaii, New Jersey, New York, Oregon, and Minnesota. In these jurisdictions, ending domicile or establishing residency in a more tax friendly state is often a key step for expats who want to reduce ongoing state tax exposure.

States with the highest tax burden for expats

Some states impose the most stringent tax policies on expats, including high income tax rates and no meaningful exclusions for foreign earned income at the state level. If you are domiciled in one of these states, relocating your domicile to a more tax friendly state can lead to substantial long term savings, provided you follow the new state’s rules and fully end residency in your prior state.

These states have high income tax rates and tax worldwide income with no exclusions, making them the least favorable for expats in terms of tax savings.

Steps to reduce state tax obligations

If you plan to avoid state tax obligations, especially from states that tax worldwide income without providing relief, consider these steps:

- Establish domicile in a tax-friendly state: Moving your official residence to a state with no income tax, like Florida, Nevada, Texas, or South Dakota, can significantly reduce your tax burden.

- Update official documents: Cancel voter registration, update your driver’s license, and transfer financial accounts to reflect your new domicile.

- File a final tax return in your previous state: This signals the end of your tax residency and helps prevent future state tax liabilities.

Additional U.S. reporting requirements – FATCA and FBAR

As a U.S. expat in Brazil, your tax obligations don’t stop at filing your federal and state tax returns. If you have foreign bank accounts or assets, you might also need to report them to U.S. authorities. While this might seem like extra paperwork, it’s essential to stay compliant and avoid hefty penalties.

FATCA (Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act)

The Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act, or FATCA, was introduced to help the IRS prevent tax evasion by U.S. citizens using foreign accounts. FATCA requires U.S. taxpayers to report certain foreign assets to the IRS. Here’s what you need to know about FATCA and its requirements:

Who needs to file under FATCA?

If you have foreign assets that exceed certain thresholds, you’ll need to report them on Form 8938, which is submitted along with your regular tax return. For single filers living abroad, the threshold is $200,000 on the last day of the tax year or $300,000 at any point during the year. For married couples filing jointly, the thresholds are doubled.

What needs to be reported?

Reportable assets under FATCA include foreign bank accounts, investment accounts, foreign stocks, and even certain pensions. Generally, any financial assets held outside the U.S. should be reviewed to determine if they need to be reported.

How to file FATCA (form 8938?

If you meet the reporting threshold, you’ll complete Form 8938 and submit it with your regular tax return (Form 1040). The form requires details like account numbers, maximum account values, and the financial institution’s location.

Example: If you hold R$1,200,000 (about $240,000) in Brazilian savings and investments, you’ll likely need to file Form 8938.

FBAR (Foreign Bank Account Report)

The Foreign Bank Account Report (FBAR) is another requirement for U.S. citizens with overseas accounts. While FATCA applies based on the value of financial assets, the FBAR requirement is specifically tied to foreign bank accounts. Here’s a breakdown:

Who needs to file FBAR?

If the combined balance of all your foreign bank accounts exceeds $10,000 at any point during the year, you’re required to file an FBAR. This rule applies even if you just temporarily crossed the $10,000 threshold. For instance, if you have two accounts—one with $5,000 and another with $6,000—you would need to file an FBAR, as the combined balance is over $10,000.

Example: If you have a Brazilian checking account with R$20,000 and a savings account with R$30,000, their combined value exceeds $10,000, and you must file an FBAR.

How to file the FBAR (fincen form 114)?

The FBAR is filed separately from your tax return and is submitted online through the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN). The form, FinCEN Form 114, requires you to report details about each foreign account, including the bank name, account number, and maximum balance during the year.

Important deadlines and penalties

The FBAR filing deadline is April 15, but there is an automatic extension until October 15 for those who miss the initial deadline. Be mindful of FBAR filing, as the penalties for not reporting eligible accounts can be severe, with fines starting at $10,000 for each unreported account.

Understanding the difference between FATCA and FBAR

While FATCA and FBAR both aim to provide the IRS with information about foreign financial accounts, they have distinct differences:

- Different thresholds: FATCA requires reporting if your foreign assets exceed $200,000 as a single filer, while FBAR applies if the total balance in all foreign accounts exceeds $10,000.

- Different filing locations: FATCA reporting (Form 8938) is filed with your federal tax return, whereas the FBAR is filed separately through FinCEN.

- Types of assets reported: FATCA requires reporting a broader range of foreign financial assets, while FBAR focuses only on foreign bank accounts.

Why do FATCA and FBAR matter for U.S. expats?

Failing to file FATCA and FBAR can result in significant penalties, so it’s essential to understand whether you’re required to report these assets. While it may seem like an extra step, filing these forms can help you stay compliant with IRS regulations and avoid unnecessary fines. If you have foreign bank accounts or financial assets, it is a good idea to consult a tax professional to help make sure you are meeting all reporting requirements.

Brazil tax obligations for U.S. expats

If you’re living in Brazil, you’ll likely need to navigate its tax system in addition to meeting your U.S. tax obligations. Brazil’s tax system includes income taxes, social contributions, and other levies, and understanding these is essential for staying compliant.

Determining tax residency in Brazil

Brazil considers you a tax resident if you meet any of these criteria:

- 183-Day Rule: You spend 183 days or more in Brazil during a calendar year.

- Permanent Visa: You hold a permanent visa and are employed or have a contract in Brazil.

- Economic Ties: Your primary economic activities or family dependents are based in Brazil.

As a tax resident, you must report your worldwide income to Brazil’s tax authorities. Non-residents are only taxed on their Brazilian-sourced income.

Brazil’s income tax rates

Brazil uses a progressive tax system for individuals. The 2024 rates are as follows:

- Up to R$28,559.70 per year: Exempt (no taxes).

- R$28,559.71 to R$34,867.80: 7.5%

- R$34,867.81 to R$45,775.56: 15%

- R$45,775.57 to R$55,973.08: 22.5%

- Above R$55,973.08: 27.5%

Example: If you earn R$100,000 annually, your taxes are calculated progressively, with 27.5% applying only to income above R$55,973.08.

Social Security Contributions (INSS)

If you’re employed in Brazil, you’ll contribute to the Instituto Nacional do Seguro Social (INSS), Brazil’s social security system.

- Employee Contribution Rates: 7.5% to 14%, depending on your income level.

- Employer Contributions: 20% of your gross salary.

These contributions are mandatory for residents and provide access to benefits like healthcare, pensions, and unemployment insurance.

Other taxes to consider

- Wealth Tax: Brazil currently does not have a nationwide wealth tax, but this could change in the future.

- Capital Gains Tax: Gains from the sale of assets in Brazil are taxed at rates from 15% to 22.5%.

- Rental Income Tax: Rental income is taxable in Brazil and must be reported monthly.

Filing deadlines and tax year in Brazil

Tax Year and Deadlines:

- Brazil’s tax year runs from January 1 to December 31.

- The filing deadline is typically April 30 of the following year.

Required Documents:

- Proof of income (e.g., salary slips or business income records).

- Records of tax deductions (e.g., health expenses or dependents).

- Investment and bank account statements.

How to File:

- Online through Brazil’s Receita Federal portal.

- Consider hiring a local accountant to help with the process, especially if Portuguese isn’t your strong suit.

U.S.-Brazil tax treaty

Unlike many countries with strong economic ties to the United States, Brazil does not have a formal tax treaty with the U.S. to prevent double taxation. This absence creates unique challenges for U.S. expats living in Brazil, as there are no direct mechanisms to allocate taxing rights between the two countries or provide reduced withholding tax rates.

However, there are strategies and tools you can use to navigate these complexities and avoid paying taxes twice.

Implications of No U.S.-Brazil Tax Treaty

- Double taxation risk: Without a treaty, income earned in Brazil may be taxed by both Brazil and the U.S., leading to potential double taxation. For example, wages, investment income, or business profits earned in Brazil are taxed by Brazilian authorities and must also be reported on your U.S. tax return.

- No reduced withholding tax rates: Tax treaties typically reduce withholding rates on income like dividends, interest, and royalties. In the absence of a treaty, standard rates apply:

- Dividends: Withholding tax of up to 15%.

- Interest: Withholding tax of 15%.

- Royalties: Withholding tax of 15% to 25%.

These rates are set by Brazilian law and cannot be reduced for U.S. taxpayers due to the lack of a treaty.

- Separate compliance requirements: Without treaty provisions, you must fully comply with the tax laws of both countries independently, including filing separate tax returns and adhering to deadlines.

Social Security Agreement (Totalization Agreement)

Managing social security contributions while living and working abroad can be challenging, especially when dealing with two countries’ systems. Fortunately, the U.S. Brazil Totalization Agreement simplifies the process for many expats, so in most cases you do not pay into both systems at the same time on the same earnings and your contributions can be counted toward future benefits in one or both countries, subject to the agreement’s rules.

What is the U.S.-Brazil totalization agreement?

Implemented in 2018, the Totalization Agreement between the U.S. and Brazil aims to:

1. Prevent double contributions to social security systems.

2. Allow workers to combine their contributions from both countries to qualify for benefits.

This agreement is a significant relief for expats and businesses, as it streamlines compliance with social security laws.

Key benefits of the agreement

- Avoid double contributions:

- If you’re temporarily working in Brazil for a U.S.-based employer, you can remain in the U.S. Social Security system and avoid contributing to Brazil’s Instituto Nacional do Seguro Social (INSS).

- Similarly, Brazilian nationals working in the U.S. for a Brazilian employer can avoid U.S. Social Security taxes.

- Combine credits for benefits:

- Contributions made to both the U.S. and Brazilian systems can be combined to meet eligibility requirements for benefits in one or both countries.

- Example: If you worked in the U.S. for 6 years and in Brazil for 4 years, the combined 10 years can help you qualify for Social Security benefits in the U.S.

- Access benefits internationally:You can receive U.S. Social Security benefits while living in Brazil, and vice versa, as long as you meet eligibility criteria.

Brazil tax filing process for U.S. expats

If you’re a tax resident in Brazil, you’re required to report your worldwide income to the Brazilian tax authorities. Here’s how the process works:

Tax year and deadlines:

- Brazil’s tax year runs from January 1 to December 31.

- The filing deadline is April 30 of the following year.

Required documents:

- Proof of income: Salary slips, freelance earnings, or investment statements.

- Records of deductions: Medical expenses, education costs, or social security contributions.

- Bank account statements (especially if assets exceed R$140,000).

How to file:

- Online through the Receita Federal’s system (Programa IRPF).

- You can download the software from the Receita Federal website.

- Many expats hire local accountants to help with the filing process, especially if they are unfamiliar with Portuguese or the system’s details.

What to declare:

- Income from Brazilian and global sources (if a tax resident).

- Financial assets in Brazil and abroad exceeding certain thresholds.

Deductions you can claim:

- Health Expenses: Medical and dental costs.

- Education Expenses: Limited deductions for yourself or dependents.

- Dependents: Fixed deductions per dependent.

Example: If you earned R$100,000 in Brazil and paid R$20,000 in medical expenses, you can deduct those costs to lower your taxable income.