Guide to U.S. expat taxes in Japan

Living in Japan is an incredible experience—modern cities, rich traditions, and amazing food all rolled into one fascinating country. But, like any big adventure, there are responsibilities to manage, and taxes are a big one. As a U.S. citizen living in Japan, you’ll have to navigate expat tax responsibilities in both countries.

The U.S. tax system is unique—it taxes its citizens no matter where they live. That means Uncle Sam wants you to file a tax return even if you're earning income in Japan.

On top of that, Japan has its own tax rules for residents and foreigners. While this might sound overwhelming, the good news is there are ways to avoid paying taxes twice.

U.S. federal tax obligations for expats

As a U.S. citizen, you're required to report your worldwide income to the IRS, no matter where you live. While this might sound overwhelming, there are several tax benefits available to expats that can significantly reduce or eliminate your U.S. tax liability.

Overview of worldwide income

The U.S. tax system mandates that citizens and resident aliens report all income from global sources. This includes:

- Employment Income: Salaries, wages, bonuses, and commissions earned in Japan or any other country.

- Self-Employment Income: Earnings from freelance work or business operations conducted abroad.

- Investment Income: Interest, dividends, capital gains, and rental income from both U.S. and foreign sources.

Regardless of where the income is earned or where you reside, it must be reported to the Internal Revenue Service (IRS).

Example: If you’re working for a Japanese company and earning ¥6,000,000 per year, that income must be reported on your U.S. tax return.

Filing requirements and thresholds

The requirement to file a U.S. tax return and pay taxes depends on your filing status, age, and gross income.

For the tax year 2024, the thresholds are as follows:

- Single Filers: Must file if gross income is at least $13,850.

- Married Filing Jointly: Must file if combined gross income is at least $27,700.

- Married Filing Separately: Must file if gross income is at least $5.

- Head of Household: Must file if gross income is at least $20,800.

These thresholds are subject to annual adjustments for inflation. It’s crucial to verify the current year’s thresholds to ensure compliance.

Key tax exclusions and credits

To alleviate the burden of double taxation, the IRS provides several provisions:

Foreign Earned Income Exclusion (FEIE)

The FEIE allows qualifying U.S. expats to exclude a certain amount of foreign-earned income from U.S. taxation. For 2023, this exclusion amount is up to $126,500.

To qualify, you must meet one of the following tests:

- Physical Presence Test: You’ve spent at least 330 full days in Japan (or another foreign country) during any 12-month period.

- Bona Fide Residence Test: You’ve spent at least 330 full days in Japan (or another foreign country) during any 12-month period.

To claim the FEIE, file Form 2555 with your U.S. tax return.

Example: If you earn $100,000 working in Japan, you could use the FEIE to exclude the entire amount from U.S. taxation, leaving you with no federal tax liability on that income.

Foreign Tax Credit (FTC)

The FTC allows you to reduce your U.S. taxes by the amount of income taxes you’ve paid to Japan. This credit is dollar-for-dollar, which means every yen paid to Japan counts against your U.S. tax bill.

Example: If you owe $10,000 in Japanese taxes and $8,000 in U.S. taxes, the FTC can cancel out your U.S. tax bill completely.

Foreign Housing Exclusion

If you spend a lot on housing in Japan, you can deduct certain expenses like rent and utilities from your U.S. taxable income. This is especially useful in high-cost cities like Tokyo.

Example: If you earn $90,000 in Japan and pay $20,000 in rent, you may be able to exclude your entire income using the FEIE and the Foreign Housing Exclusion.

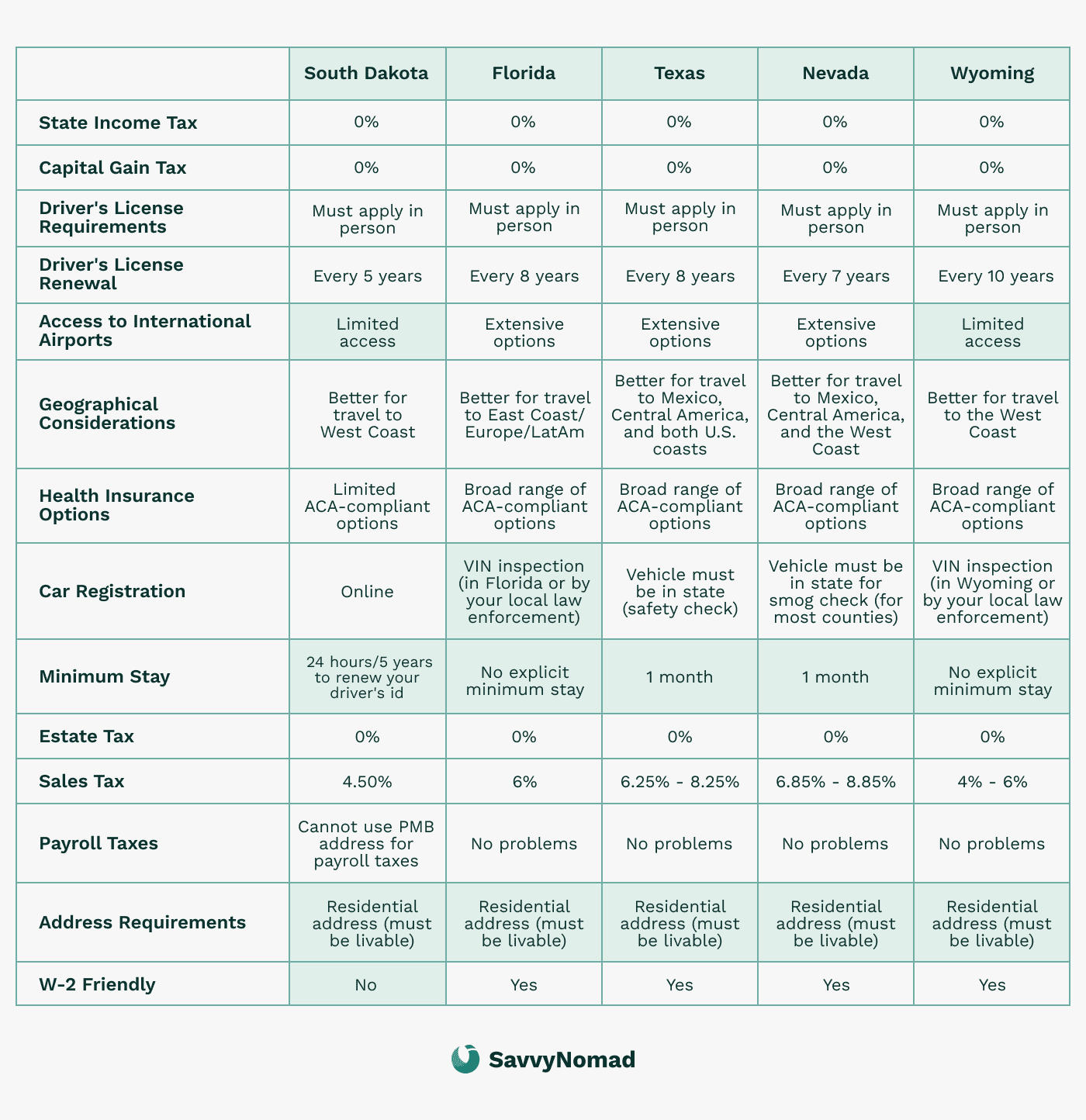

State tax obligations for the U.S. expats in Japan

Federal taxes aren’t the only thing to think about when you move abroad. Some states in the U.S. might still want a slice of your income, even while you’re living in Japan. Whether you owe state taxes depends on where you lived before you moved and how well you’ve cut ties with your former state.

Determining state domicile

State tax obligations depend on whether your previous state of residence considers you a tax resident. Generally, your state of domicile—your permanent home—determines whether you owe state taxes. If you’ve moved to Japan but still maintain strong ties to your former state, such as owning property or holding a driver’s license, you may still be considered a tax resident.

To avoid ongoing state tax obligations, it’s often necessary to formally sever ties with your previous state of residence.

Here’s a breakdown of states by tax treatment:

States with no tax on worldwide income for non-residents

These states provide favorable tax treatment for expats, as they do not impose taxes on global income if you can establish non-resident status:

- Colorado

- Connecticut

- Delaware

- Massachusetts

- Minnesota

- Missouri

- North Dakota

- Oregon

- Pennsylvania

- Virginia

- West Virginia

Expats from these states may not need to take significant steps to maintain their non-resident status once they relocate. This group of states offers considerable savings by not taxing worldwide income, making them favorable options for expats.

States that tax worldwide income but offer FEIE

These states tax worldwide income but provide some relief to expats by allowing a Foreign Earned Income Exclusion (FEIE). For the 2024 tax year, the FEIE lets expats exclude up to $126,500 of foreign-earned income from state income tax.

- Alabama

- Arizona

- Georgia

- Idaho

- Illinois

- Indiana

- Iowa

- Kansas

- Kentucky

- Maine

- Michigan

- Ohio

- Oklahoma

- Rhode Island

- South Carolina

- Utah

- Vermont

While these states tax global income, expats can reduce their tax liability with the FEIE, which allows them to exclude a significant portion of their foreign earnings.

States that tax worldwide income with no FEIE

These states tax worldwide income but do not provide a Foreign Earned Income Exclusion, resulting in higher potential tax burdens for expats, as there is no mechanism to offset foreign-earned income:

- Arkansas

- Indiana

- Kentucky

- Louisiana

- Maine

- Maryland

- Mississippi

- Montana

- Nebraska

- New Mexico

- North Carolina

- Wisconsin

Expats domiciled in these states face more significant tax liabilities on their global income due to the lack of FEIE, which makes establishing domicile elsewhere more appealing.

States with the highest tax burden for expats

Some states impose the most stringent tax policies on expats, including high income tax rates and no exclusions for foreign-earned income. If you’re domiciled in one of these states, relocating your domicile to a more tax-friendly state can lead to substantial savings.

These states have high income tax rates and tax worldwide income with no exclusions, making them the least favorable for expats in terms of tax savings.

Steps to reduce state tax obligations

If you plan to avoid state tax obligations, especially from states that tax worldwide income without providing relief, consider these steps:

- Establish domicile in a tax-friendly state: Moving your official residence to a state with no income tax, like Florida, Nevada, Texas, or South Dakota, can significantly reduce your tax burden.

- Update official documents: Cancel voter registration, update your driver’s license, and transfer financial accounts to reflect your new domicile.

- File a final tax return in your previous state: This signals the end of your tax residency and helps prevent future state tax liabilities.

Additional U.S. reporting requirements – FATCA and FBAR

Living in Japan as a U.S. expat brings unique responsibilities, especially when it comes to reporting foreign accounts and assets. Beyond your annual tax return, the U.S. requires additional forms to monitor overseas financial activities. While this might seem like extra paperwork, staying compliant will save you from hefty penalties.

FATCA (Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act)

The Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act, or FATCA, was introduced to help the IRS prevent tax evasion by U.S. citizens using foreign accounts. FATCA requires U.S. taxpayers to report certain foreign assets to the IRS. Here’s what you need to know about FATCA and its requirements:

Who needs to file under FATCA?

If you have foreign assets that exceed certain thresholds, you’ll need to report them on Form 8938, which is submitted along with your regular tax return. For single filers living abroad, the threshold is $200,000 on the last day of the tax year or $300,000 at any point during the year. For married couples filing jointly, the thresholds are doubled.

What needs to be reported?

Reportable assets under FATCA include foreign bank accounts, investment accounts, foreign stocks, and even certain pensions. Generally, any financial assets held outside the U.S. should be reviewed to determine if they need to be reported.

How to file FATCA (form 8938)?

Filing the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA) form, also known as Form 8938, is a crucial step for U.S. expats in Japan who have foreign financial assets.

Here’s a step-by-step guide on how to file FATCA:

- Determine if you need to file: You must file Form 8938 if you have foreign financial assets with an aggregate value exceeding $50,000 on the last day of the tax year or $75,000 at any time during the tax year.

- Gather required information: You’ll need to provide details about your foreign financial assets, including the name and address of the financial institution, the account number, and the highest value of the account during the tax year.

- Complete Form 8938: You can download Form 8938 from the IRS website or use tax software to complete it. Make sure to attach it to your tax return (Form 1040).

- Report foreign financial assets: You’ll need to report the following types of foreign financial assets:

- Foreign bank accounts

- Foreign securities accounts

- Foreign mutual funds

- Foreign hedge funds

- Foreign private equity funds

- Foreign real estate

- File Form 8938 with your tax return: Attach Form 8938 to your tax return (Form 1040) and file it with the IRS by the tax filing deadline.

By following these steps, you can ensure compliance with FATCA requirements and avoid potential penalties.

FBAR (Foreign Bank Account Report)

The Foreign Bank Account Report (FBAR) is another requirement for U.S. citizens with overseas accounts. While FATCA applies based on the value of financial assets, the FBAR requirement is specifically tied to foreign bank accounts. Here’s a breakdown:

Who needs to file FBAR?

If the combined balance of all your foreign bank accounts exceeds $10,000 at any point during the year, you’re required to file an FBAR. This rule applies even if you just temporarily crossed the $10,000 threshold. For instance, if you have two accounts—one with $5,000 and another with $6,000—you would need to file an FBAR, as the combined balance is over $10,000.

How to file the FBAR (fincen form 114)?

The FBAR is filed separately from your tax return and is submitted online through the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN). The form, FinCEN Form 114, requires you to report details about each foreign account, including the bank name, account number, and maximum balance during the year.

Important deadlines and penalties

The FBAR filing deadline is April 15, but there is an automatic extension until October 15 for those who miss the initial deadline. Be mindful of FBAR filing, as the penalties for not reporting eligible accounts can be severe, with fines starting at $10,000 for each unreported account.

Understanding the difference between FATCA and FBAR

While FATCA and FBAR both aim to provide the IRS with information about foreign financial accounts, they have distinct differences:

- Different thresholds: FATCA requires reporting if your foreign assets exceed $200,000 as a single filer, while FBAR applies if the total balance in all foreign accounts exceeds $10,000.

- Different filing locations: FATCA reporting (Form 8938) is filed with your federal tax return, whereas the FBAR is filed separately through FinCEN.

- Types of assets reported: FATCA requires reporting a broader range of foreign financial assets, while FBAR focuses only on foreign bank accounts.

Why do FATCA and FBAR matter for U.S. expats?

Failing to file FATCA and FBAR can result in significant penalties, so it’s essential to understand whether you’re required to report these assets. While it may seem like an extra step, filing these forms can help ensure compliance with IRS regulations and avoid unnecessary fines. If you have foreign bank accounts or financial assets, it’s a good idea to consult a tax professional to ensure you’re meeting all reporting requirements.

Japan tax obligations for U.S. expats

As an expat living in Japan, you’re not just accountable to Uncle Sam; you’ll also need to comply with Japanese tax laws. Japan’s tax system has its own rules, rates, and deadlines, so understanding your obligations will help you stay on top of things and avoid penalties.

Determining tax residency in Japan

Your tax residency determines what income you need to report in Japan. There are two main categories:

Resident:

- You’ve lived in Japan for 183 days or more during a calendar year.

- You maintain a permanent home or have significant personal and economic ties to Japan.

- Residents are taxed on their worldwide income, including income earned in the U.S.

Non-Resident:

- You’ve spent less than 183 days in Japan and don’t have a permanent home there.

- Non-residents are only taxed on income earned within Japan.

Example: If you’ve been working in Tokyo for most of the year, you’ll likely be considered a tax resident and must report both Japanese and foreign income.

Japanese income tax rates

Japan uses a progressive tax system, meaning your tax rate increases as your income rises. For 2024, here are the brackets:

- Up to ¥1,950,000: 5%

- ¥1,950,001 to ¥3,300,000: 10%

- ¥3,300,001 to ¥6,950,000: 20%

- ¥6,950,001 to ¥9,000,000: 23%

- ¥9,000,001 to ¥18,000,000: 33%

- Over ¥18,000,000: 40%

Example: If you earn ¥5,000,000 in Japan, your taxes are calculated like this:

- 5% on the first ¥1,950,000.

- 10% on the next ¥1,350,000.

- 20% on the remaining ¥1,700,000.

Local Inhabitant Taxes

In addition to national income tax, Japan imposes local taxes:

- Rate: Typically around 10% of your taxable income.

- These are paid to your local city or ward.

Example: If your taxable income is ¥5,000,000, you’ll owe about ¥500,000 in local taxes.

Social Security contributions

If you’re working in Japan, you’ll also contribute to the country’s social security system:

- National Health Insurance: Covers medical costs; contributions vary based on income.

- Pension System: Employees contribute around 9.15% of their salary, matched by employers.

Pro Tip: If you leave Japan, you can claim a partial refund of your pension contributions.

Filing deadlines and tax year in Japan

Tax Year: January 1 to December 31.

Filing Deadline: March 15 of the following year.

Documents Needed:

- Salary statements (gensen choshuhyo).

- Bank and investment records.

- Proof of deductions, such as medical expenses or charitable donations.

Most salaried employees don’t need to file a tax return because taxes are withheld from their paychecks. However, you’ll need to file if you:

- Earn income outside your job (e.g., freelance or rental income).

- Want to claim deductions.

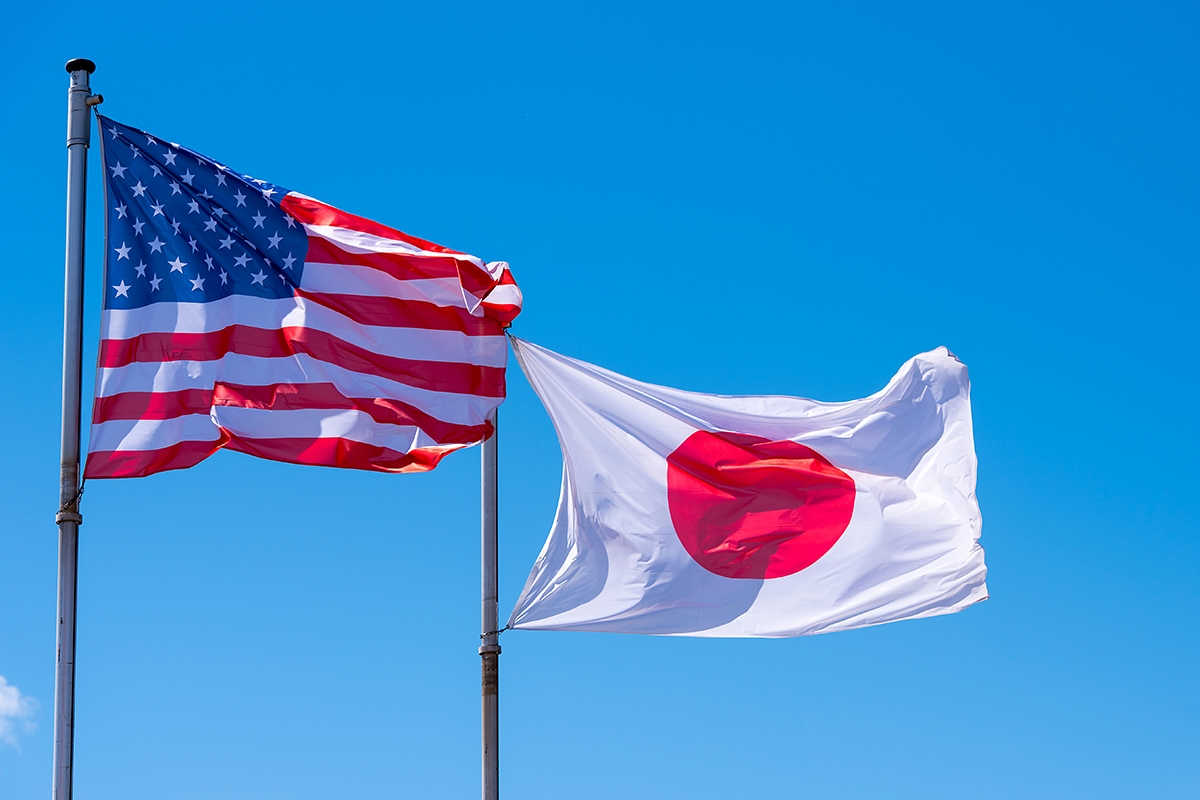

U.S.- Japan tax treaty

One of the biggest perks of living in Japan as a U.S. expat is the U.S.-Japan Tax Treaty, which exists to prevent double taxation and clarify which country taxes different types of income. By understanding and using the treaty, you can streamline your tax obligations and potentially save money.

Purpose of the U.S.-Japan tax treaty

The main objectives of the tax treaty are to:

- Prevent Double Taxation: Ensure you aren’t taxed on the same income by both countries.

- Define Tax Rights: Establish clear rules on which country has taxing authority over specific types of income.

- Social Security Coordination: The treaty includes a Totalization Agreement to avoid paying into both the U.S. and Japanese social security systems.

By using the treaty, you can align your U.S. and Japann tax filings to avoid paying more than you owe.

For U.S. expats, the treaty helps lower the risk of double taxation by allowing foreign tax credits, setting reduced tax rates on specific income types, and establishing residency and income allocation rules.

Key treaty provisions

- If you work in Japan, your salary is primarily taxed in Japan.

- You still report this income on your U.S. tax return, but you can use the Foreign Tax Credit (FTC) or Foreign Earned Income Exclusion (FEIE) to avoid U.S. taxes.

- Dividends and Interest:

- Dividends from Japanese investments are taxed in Japan, but the treaty caps the rate at 10%.

- Interest income is typically taxed only in your country of residence.

- Capital Gains: Capital gains from selling assets, like stocks, are generally taxed in your country of residence. If you’re a resident of Japan, Japan gets the taxing rights.

- Pensions and Retirement Income: Most pensions are taxed in your country of residence. For example, U.S.-based retirement income is usually taxed in Japan if you’re a Japanese resident, with some exceptions.

Employment Income:

Social Security Agreement (Totalization Agreement)

One of the challenges of living and working abroad is navigating social security systems. As a U.S. expat in Japan, you might wonder whether you need to pay into both countries’ systems or how your contributions will affect your future benefits. Thankfully, the U.S.-Japan Totalization Agreement simplifies things.

The Totalization Agreement between the U.S. and Japan ensures that expats don’t have to pay into both countries’ social security systems simultaneously. It also helps you combine your contributions from both countries to qualify for benefits.

Key benefits

- Avoid Double Contributions:

- If you’re in Japan temporarily (5 years or less) working for a U.S.-based employer, you stay in the U.S. Social Security system and avoid Japan’s contributions.

- Japanese citizens in the U.S. get similar treatment.

- Combine Credits: Contributions in both countries can be combined to meet eligibility requirements for benefits in either system.

- Access Benefits Internationally: You can receive social security benefits from one country even while living in the other.

Claiming treaty benefits

To take advantage of the tax treaty, U.S. expats may need to file specific forms with the IRS:

- Form 8833 (Treaty-Based Return Position Disclosure): This form is required if you’re claiming treaty benefits to reduce or eliminate your U.S. tax liability on income earned in Japan.

- Form 1116 (Foreign Tax Credit): Use this form to claim credits for taxes paid to Japan on income also taxable by the U.S., helping to avoid double taxation.

Residency and tie-breaker rules

The treaty also includes “tie-breaker” rules to help determine tax residency if both countries consider you a resident. Here’s how the treaty resolves conflicts in residency status:

- Permanent Home: Priority is given to the country where you maintain a permanent home.

- Center of Vital Interests: If you have permanent homes in both countries, the country where you have stronger personal and economic ties (center of vital interests) takes precedence.

- Habitual Abode: If neither of the above determines residency, the country where you habitually reside is considered your primary tax residence.

These tie-breaker rules help avoid conflicts over tax residency and ensure that your tax obligations are clear.

Japan tax filing process for U.S. expats

As a U.S. expat living in Japan, you’ll likely need to file tax returns in both countries. Managing this dual responsibility might seem overwhelming, but it’s manageable with the right approach. Let’s break it down.

If you’re a resident in Japan, you’re required to file a Japanese tax return and report your worldwide income. Here’s how to navigate the process:

- Tax Year and Deadlines:

- Japan’s tax year runs from January 1 to December 31.

- The filing deadline is March 15 of the following year.

- Taxes owed must also be paid by this date.

- What You’ll Need to File:

- Gensen Choshuhyo (源泉徴収票): This is a summary of your annual income and taxes withheld, provided by your employer.

- Bank and investment records for interest, dividends, and capital gains.

- Proof of deductible expenses (e.g., medical costs, insurance premiums).

- How to File:

- Online: Japan’s tax authority, the National Tax Agency (NTA), provides an online filing system, but it’s primarily in Japanese.

- In-Person: Visit your local tax office to file a paper return.

- Hire a Tax Professional: A bilingual tax consultant can help if you’re unfamiliar with the language or the process.

- Deductions You Can Claim:

- Health Insurance Premiums: Payments to Japan’s National Health Insurance system.

- Pension Contributions: Payments into Japan’s pension system.

Dependent Deductions: For family members who qualify as dependents.

Rental income Taxes

As a U.S. expat in Japan, you may have rental income from a property in the U.S. or Japan.

Tax implications for rental income in Japan

If you have rental income from a property in Japan, you’ll need to report it on your U.S. tax return. Here are the tax implications:

- Rental income is considered passive income: Rental income is considered passive income and is subject to U.S. taxation.

- You may be eligible for the Foreign Earned Income Exclusion (FEIE): If you meet certain requirements, you may be eligible for the FEIE, which can exclude up to $126,500 of foreign-earned income from U.S. taxation.

- You may be subject to Japanese taxes: As a U.S. expat in Japan, you may be subject to Japanese taxes on your rental income. You can claim a foreign tax credit on your U.S. tax return to avoid double taxation.

- You’ll need to file Form 8938: If you have foreign financial assets, including rental income, you’ll need to file Form 8938 with your tax return.

Example: If you earn ¥2,000,000 in rental income from a property in Japan, you’ll need to report this income on both your Japanese and U.S. tax returns. You can use the foreign tax credit to offset any Japanese taxes paid, reducing your U.S. tax liability.

By understanding these tax implications and filing the necessary forms, you can ensure compliance with both U.S. and Japanese tax laws and avoid double taxation.