U.S. tax guide for American nomads

Living as a digital nomad opens up a world of adventure and flexibility and brings unique tax challenges. As you navigate through different states and countries, understanding your tax obligations becomes crucial.

From federal to state taxes and local foreign tax obligations, we cover everything you need to know to stay compliant and make informed financial decisions while enjoying your nomadic lifestyle.

State taxes

State tax laws differ significantly across the U.S. Many states with an income tax treat their residents as taxable on worldwide income until they truly end domicile, while some states have no state income tax at all and a few have clearer paths to nonresident status.

Only some states closely follow federal exclusions or credits for foreign earned income, so where you are “from” for state purposes can matter just as much as your federal strategy.

For digital nomads and expats, it helps to think of states in three broad groups based on how they treat residents and how predictable it is to stop being a tax resident:

Category 1 – Worldwide-income states (domicile and facts-and-circumstances dominate)

These states generally tax residents on worldwide income until domicile is truly ended. They rely heavily on “intent and presence” tests and often have aggressive audit behavior for people who move abroad. Some have limited expat safe harbors, but those are usually temporary and documentation-heavy.

- Arkansas

- Arizona

- California (546-day foreign-employment safe harbor (FTB Pub 1031))When the rule is followed precisely, it generally holds up well on audit.

The state expects clear documentation showing that: The key audit focus is documentation — flight records, work contracts, and housing leases are essential.

Auditors are more likely to challenge short breaks or inconsistent records than the rule itself.When the facts fit, the California safe harbor is respected in practice, but it only provides temporary nonresident protection — it does not change domicile.It’s best suited for defined foreign assignments (e.g., 18-24 month projects) where you’ll return afterward.

For long-term or indefinite expatriation, formally ending California domicile (e.g., establishing Florida domicile) is simpler, more durable, and easier to defend.Once domicile is re-established elsewhere, there’s no need for contract or day-count tracking — the safe harbor becomes unnecessary.- The taxpayer was outside California under an employment contract for at least 546 consecutive days, and

- Visits back to California totaled 45 days or less in any calendar year.

- Connecticut

- District of Columbia

- Delaware

- Hawaii

- Idaho

- Louisiana

- Michigan

- Maine

- Maryland

- Massachusetts

- Minnesota

- Missouri

- Mississippi

- Montana

- Nebraska

- New Jersey

- New Mexico

- New York (548-day foreign-assignment safe harbor (Nonresident Audit Guidelines))

This safe harbor is narrower and applied more strictly than California’s. To qualify, the taxpayer must:

It’s enforceable if documented well, but NY examiners are aggressive about counting days and verifying housing status.

They often request passport stamps, travel logs, and employer verification. When all requirements are met, the rule is respected in practice, but, like California’s, it confers temporary nonresident status rather than ending domicile.It’s most useful for clearly defined foreign assignments under a written employment contract.

For long-term expats or entrepreneurs abroad, it’s usually simpler and lower-risk to end New York domicile entirely (e.g., by establishing domicile in Florida or another no-tax state). That eliminates day-count monitoring and domicile-related audits once the new domicile is clearly documented.- Be assigned full-time abroad for at least 548 consecutive days,

- Maintain no permanent place of abode in New York during that period, and

- Limit New York visits to 90 days or less per year.

- North Carolina

- North Dakota

- Oklahoma

- Oregon (does not recognize the FEIE)

- Rhode Island

- Vermont

- Virginia

- West Virginia

- Wisconsin

In practice, if one of these is your domicile, the safest long-term path is usually to formally end that domicile (for example, by establishing domicile in a no-tax state like Florida) and to clearly document the move, rather than relying forever on day-count rules alone.

Category 2 – Federal-AGI states (federal exclusions may flow through; residency still rules)

These states start from federal adjusted gross income (AGI), so some federal items such as the Foreign Earned Income Exclusion may flow through into the state return, unless the state has explicitly decoupled. However, residency rules still control: if the state treats you as a resident, it can effectively pull worldwide income into its base even if the starting point is federal AGI.

- Alabama

- Colorado

- Georgia

- Illinois

- Indiana

- Iowa

- Kansas

- Kentucky

- South Carolina

- Utah

For nomads, this can sometimes be more forgiving than a pure worldwide-income state because excluded foreign income may be left out at the state level, but the key questions are still: “Are you a resident?” and “What counts as in-state source income?”

Category 3 – Clear exit or no-income-tax states

This group consists of states with no broad state individual income tax plus a few with unusually clear nonresident rules. Once you genuinely establish and document domicile in one of these states and cut ties with your old state, ongoing state income tax on foreign wages often falls away, subject to any trailing income from the old state.

This group includes the classic no-tax states such as Alaska, Florida, Nevada, South Dakota, Texas, Washington, and Wyoming, plus states with very clear nonresident rules such as Pennsylvania (short day-count plus a clear “no Pennsylvania abode + abode elsewhere all year” test) and Ohio (nonresident affidavit plus a contact-day rule).

For nomads, these can offer a more predictable long-term structure once domicile is properly established and documented.

How state tax laws vary for nomads

State tax laws differ significantly across the U.S. Many states tax their residents on worldwide income if they have a state income tax, while some states have no state income tax at all and others focus more on income sourced to the state. Only some states closely follow federal exclusions or credits for foreign earned income.

On the other hand, states like California and New York have stringent tax laws and higher tax rates, which can be burdensome for those frequently moving.

Strategies for minimizing state tax obligations

To minimize state tax obligations, consider the following strategies:

- Choose a tax-friendly state: Establish your domicile in a state with no or low state income taxes.

- Maintain proper documentation: Keep records of your physical presence, leases, utility bills, and other documents that prove your domicile.

- Use domicile services: Utilize services like those offered by SavvyNomad to help establish and maintain residency in tax-friendly states.

- Consult with experts: Work with tax professionals like Nomad Tax to ensure compliance and optimize your tax strategy.

By understanding these considerations and implementing effective strategies, you can manage your state tax obligations more efficiently and focus on enjoying your nomadic lifestyle.

Best and worst domicile states for nomads

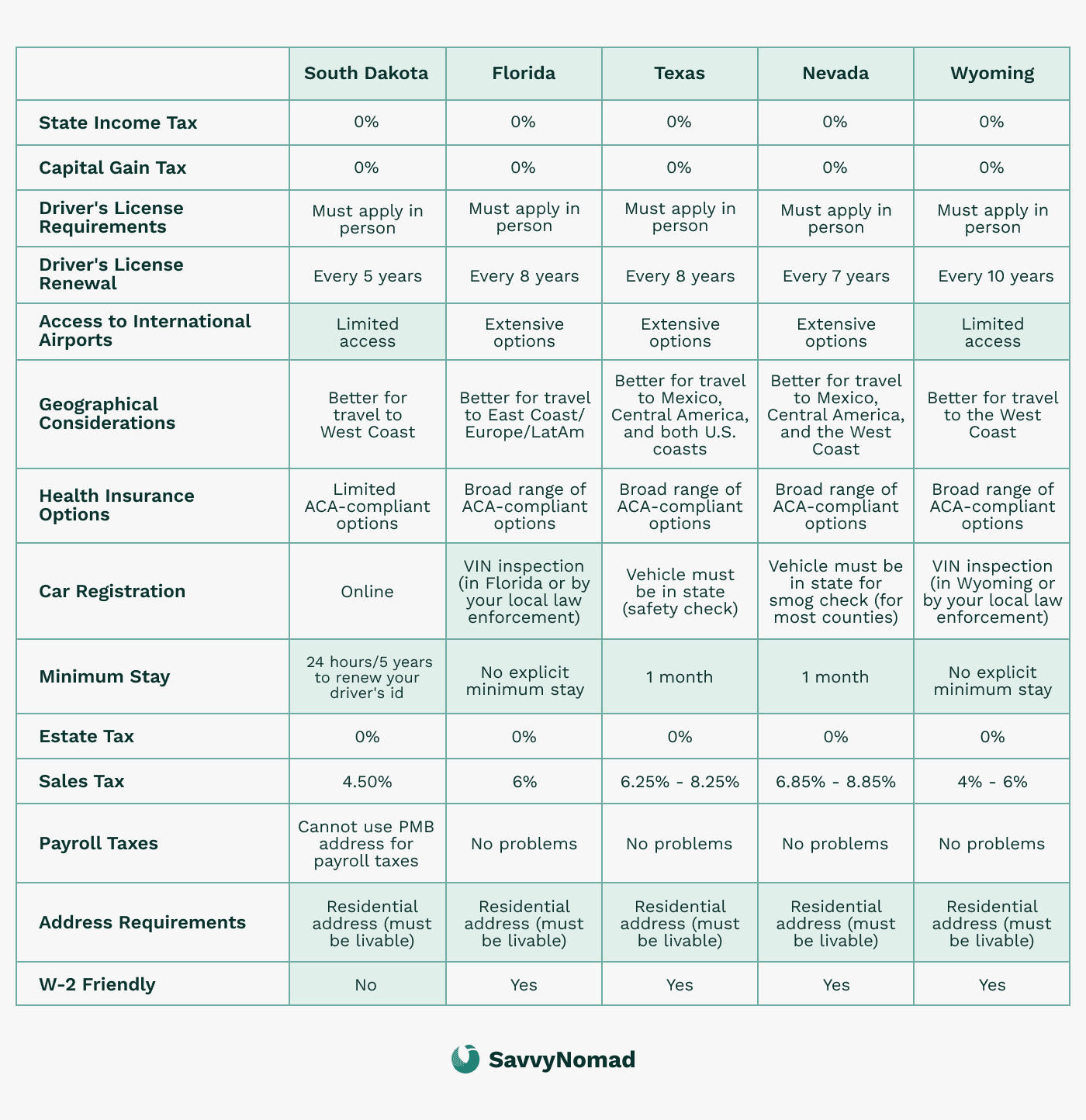

Best states for tax purposes

Certain states are particularly favorable for digital nomads due to their tax policies and ease of establishing residency:

- Florida: No state income tax, straightforward residency process, and no vehicle inspection required.

- South Dakota: No state income tax, minimal physical presence required, and simple vehicle registration. However, it is important to note that South Dakota does not offer unemployment insurance for individuals who are not physically working within the state. This can be a disadvantage, especially for employed nomads who might seek unemployment benefits.

- Nevada: No state income tax, but requires a 30-day stay to establish residency and annual vehicle emissions tests.

- Texas: No state income tax, but requires an annual vehicle safety inspection and a 30-day residency period before obtaining a state ID.

- Wyoming: No state income tax, but more challenging to establish a residential address.

These states offer significant tax savings and simplified tax management, making them attractive choices for nomads.

Worst states for tax purposes

Certain states impose high tax rates and have stringent residency requirements, making them less favorable for digital nomads:

- California: High state income tax rates, tax on worldwide income, and strict residency rules. California is also particularly aggressive in challenging domicile claims, often conducting thorough residency audits.

- Hawaii: High state income tax rates and stringent residency requirements.

- New Jersey: High state income taxes, complex tax laws, and aggressive enforcement. New Jersey, similar to California, is known for challenging domicile claims and conducting audits. Additionally, New Jersey enforces the “convenience of the employer” rule, meaning that remote workers for NJ-based companies might still owe NJ state taxes even if they live and work in another state.

- New York: High state income taxes, aggressive tax enforcement, and residency audits. New York is another state that is notably aggressive in questioning domicile status and pursuing claims against residents. Like New Jersey, New York also applies the “convenience of the employer” rule, which can lead to double taxation for remote workers living out of state.

- Virginia: High state income taxes and rigorous enforcement of tax residency rules. Virginia is also aggressive in challenging domicile claims, making it difficult for nomads to establish and maintain non-residency status.

These states can be financially burdensome for nomads due to their high tax obligations and complex tax laws.

Foreign domicile vs U.S. state domicile for nomads

As a U.S. citizen or long-term green card holder, you remain subject to U.S. federal income tax on your worldwide income even if you move abroad. What can change, however, is your state tax position.

For digital nomads and expats, there are two broad ways this plays out:

- You keep a U.S. state domicile (for example, in a high-tax Category 1 state or a no-tax Category 3 state).

- You ultimately establish a foreign domicile in another country and cut ties with your prior U.S. state.

From a state-tax perspective, these paths are not equivalent in terms of complexity, documentation, and audit risk.

What “foreign domicile” really involves

Establishing a genuine foreign domicile usually means more than just renting an Airbnb or staying on a tourist visa. In practice, it often involves things like:

- Securing a long-term visa or residency permit in the foreign country.

- Having a foreign lease or property deed that shows a real, ongoing home abroad.

- Obtaining a foreign tax ID or registration and, in many cases, filing and paying income tax there.

- Updating banking and ID records so that your foreign address and status appear consistently on official documents.

For expats who come from sticky Category 1 states, the practical reality is that claiming “I now have a foreign domicile” can be both factually correct and still heavily scrutinized. You may need to show that you both:

- Built a real life abroad (residency permit, home, foreign tax residence), and

- Truly unwound your prior state ties (no accessible home there, limited days, severed voter registration where appropriate, etc.).

Even then, high-tax states may test your story in an audit, especially if you still have substantial economic ties or periodically return for extended stays.

Choosing a U.S. state domicile instead of foreign domicile

Because of that complexity, many U.S. nomads and expats choose to:

- Establish domicile in a tax-friendly U.S. state with clear rules (for example, Florida, Texas, or another Category 3 state), and

- Then live abroad as a resident of that U.S. state, rather than claiming a foreign domicile for state purposes.

If you can clearly establish domicile in a no-income-tax state and cut domicile from your previous state, the long-term state-tax picture often becomes simpler:

- You typically no longer need to rely on a foreign-domicile argument to avoid your old state’s worldwide taxation.

- Your ongoing state exposure is mainly limited to any income derived from old-state sources (for example, rental property or a business that remains there).

- You can still live abroad as long as you respect any state-specific rules on what it means to keep that new domicile (for example, maintaining an address, ID, and a credible connection to the state).

Foreign domicile is not “wrong” or unsafe; it is simply more paperwork- and facts-heavy, and it can be harder to defend in front of a high-tax state that believes you never really left.

How this plays with safe harbors and “expat rules”

Some Category 1 states have explicit “foreign assignment” safe harbors, such as:

- California’s 546-day employment-abroad rule, and

- New York’s 548-day foreign assignment rule with strict limits on days back and no New York permanent place of abode.

Your framework treats these as useful but narrow tools:

- They can temporarily treat you as a nonresident while you are abroad under a qualifying assignment.

- They do not permanently change domicile by themselves.

- They require tight documentation (contracts, day counts, housing status), and audits tend to focus on breaking the conditions.

For long-term, open-ended nomad life, it is usually simpler and lower risk to:

- Formally end domicile in the high-tax state, and

- Build a new domicile in a clear no-tax or low-tax state,

rather than relying indefinitely on safe harbors that were designed for finite foreign assignments.

How to choose a state that aligns with your tax goals

Selecting the right state for your domicile involves considering several factors:

- Tax rates and policies: Evaluate state income tax rates and how they apply to your income, including any foreign income.

- Residency requirements: Understand the residency requirements for each state and ensure you can meet them consistently.

- Overall financial impact: Consider the total financial implications, including sales tax, property tax, and other local taxes.

- Lifestyle preferences: Factor in the cost of living, climate, and other personal preferences that affect your quality of life.

Domicile services

At SavvyNomad, we provide domicile services designed to make your life easier as a digital nomad or American expat. Our services include helping you prepare and organize the documents used to establish and maintain legal residency in zero-income tax states, such as declarations of domicile, leases or utility documents, and supporting ID.

We guide you through state-specific residency steps and can coordinate mail forwarding and assistance with vehicle registration and, if you are eligible, voter registration. We specialize in helping clients pursue residency in tax-friendly states like Florida, with South Dakota discontinued due to legislative changes and Nevada planned to be launched soon. We help you put the paperwork together, but banks and state agencies make their own decisions, no outcome is guaranteed, and prior-state rules may still apply.

Benefits of domicile services for American expats

Using our domicile services offers several significant benefits:

- Tax savings: Establishing residency in a no-income tax state can dramatically reduce your tax burden.

- Compliance: We help you meet all legal requirements, preventing complications with multiple state tax claims.

- Convenience: Our services streamline your legal and administrative obligations, giving you more time to enjoy your nomadic lifestyle.

Federal taxes

U.S. tax and reporting obligations for nomads

As an American citizen, you’re required to pay taxes on your worldwide income, regardless of where you reside. This means that even if you’re living and earning money abroad, you must report all income to the IRS. Additionally, you must report specified foreign financial assets exceeding certain thresholds using IRS Form 8938.

Filing requirements

You need to file a Form 1040, the U.S. individual income tax return, annually. Additionally, if you have foreign bank accounts or investments, you may need to file Schedule B, and possibly the Foreign Bank Account Report (FBAR) and/or Form 8938 under FATCA requirements.

Exemptions from filing requirements: There are certain scenarios where digital nomads might be exempt from federal filing requirements. Specifically, if you do not meet the minimum income threshold for the year, you may not need to file a tax return.

The IRS provides a tool that can help determine whether you need to file a return based on your income, filing status, and age. For more details, you can check the IRS guide on whether you need to file a tax return.

Key deadlines and extensions

The standard deadline for filing U.S. taxes is April 15th. However, expats are granted an automatic two-month extension until June 15th. It's important to note that while the filing deadline is extended, any payments owed are still due by April 15th.

If you don't pay by this date, interest will accrue on any unpaid amounts, even if you file by the extended June 15th deadline.

If needed, you can request a further extension to October 15th by filing Form 4868.

Filing and paying on time helps avoid penalties and interest charges.

Foreign Earned Income Exclusion (FEIE)

The Foreign Earned Income Exclusion (FEIE) allows U.S. citizens and resident aliens who live and work abroad to exclude a significant portion of their foreign-earned income from U.S. federal income tax. For the 2024 tax year, the exclusion limit is $126,500.

How to claim FEIE (Form 2555)

To claim FEIE, you must file Form 2555 along with your annual tax return (Form 1040). This form details your foreign-earned income and verifies your eligibility based on either the Physical Presence Test or the Bona Fide Residence Test.

Benefits and limitations of FEIE

Benefits:

- Tax savings: Reduces taxable income, potentially lowering your overall tax bill.

- Dual taxation relief: Helps avoid being taxed by both the U.S. and your host country on the same income.

Limitations:

- Income cap: Only foreign-earned income up to the exclusion limit ($120,000 for 2023/$126,500 for 2024) is covered.

- Non-inclusive of all income: Investment income and other non-earned income do not qualify.

- Requirement consistency: Requires consistent annual filing to maintain eligibility without a five-year revocation period.

Foreign Tax Credit (FTC)

The Foreign Tax Credit (FTC) is designed to help U.S. citizens and resident aliens who pay income taxes to foreign governments on income earned abroad. The FTC is a key tool for mitigating double taxation and helping reduce the risk of being taxed on the same income in both the U.S. and foreign countries.

The FTC allows these taxpayers to offset some or all of the income taxes paid to foreign countries against their U.S. tax liabilities, subject to various limits and rules, which can lessen or sometimes eliminate double taxation on the same income.

State-level Foreign Tax Credits (FTC)

At the federal level, the Foreign Tax Credit is a key tool to reduce double taxation when you pay income tax to a foreign country. At the state level, however, the picture is very uneven: many states only credit taxes paid to other U.S. states or cities, and only a smaller group offers any credit for foreign income taxes at all.

Broadly, the state-level foreign tax credit landscape looks like this:

States with a general foreign income-tax credit for residents

These states have a resident credit that can apply to national-level foreign income taxes, subject to documentation and limits:

Arizona, Hawaii, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Montana, North Carolina.

Montana explicitly reduces the state credit if you also claim a federal FTC on the same income, and in practice other states tend to enforce a similar “no double benefit” principle even if it is not spelled out in the statute.

States that only credit certain Canadian taxes

These states may provide a foreign tax credit, but only for certain Canadian taxes (for example, on Canadian-sourced employment or pension income) and usually require very specific documentation:

Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, New York, Vermont.

States with narrow or special-purpose foreign tax credits

A few states have foreign tax credits that are quite narrow:

- Alabama – credit is limited to certain pass-through entity (PTE) level foreign income taxes, and the scope is narrow and often scrutinized.

- Virginia – credit is limited to certain foreign pension or retirement income tied to prior foreign employment.

Across all of these states, several common themes apply:

- The foreign levy usually has to be a true net income tax (not a wealth tax, solidarity levy, or pure social contribution).

- The same income must be taxed by both the foreign jurisdiction and the state.

- The credit is capped at the state tax on that double-taxed income, and carry-forwards are limited or unavailable.

- Documentation is critical: proof of payment, copies of foreign returns or assessments, translations if needed, and a tie-out schedule showing that the foreign-taxed income lines up with the items reported on the state return.

For a working U.S. digital nomad, the practical takeaway is that your federal FTC is only half the story: your state of domicile, and whether it offers any foreign income-tax credit at all, can meaningfully change your overall effective tax rate. When you’re choosing a domicile and planning your structure, you want to think about both how easy it is to stop being a resident and whether the state will give you any relief for foreign taxes once you are a resident there.

Eligibility criteria and claiming process (Form 1116)

To qualify for the FTC, the foreign tax must be a mandatory income tax imposed by a foreign country. To claim the FTC, you must fill out Form 1116 and attach it to your U.S. tax return (Form 1040). This form requires you to detail the foreign taxes paid, convert them to U.S. dollars, and calculate the allowable credit.

Differences between FEIE and FTC

- FEIE: Allows you to exclude a certain amount of foreign-earned income from U.S. taxation (up to $120,000 for 2023/ $126,500 for 2024).

- FTC: Provides a credit for foreign taxes paid, applicable to both earned and unearned income, reducing your U.S. tax liability dollar-for-dollar.

- Combination: You can use FEIE for earned income up to the exclusion limit and FTC for any excess income or for unearned income. However, you cannot use both on the same income.

Foreign Housing Exclusion

The Foreign Housing Exclusion (FHE) allows U.S. taxpayers living abroad to exclude certain housing costs from their taxable income. This can include expenses like rent, utilities, and other housing-related costs. The primary goal of the FHE is to reduce the tax burden on expatriates by excluding these costs from U.S. taxation.

Eligibility criteria and how to claim it

To qualify for the FHE, you must:

- Have a tax home in a foreign country.

- Meet either the bona fide residence test (being a resident of a foreign country for an entire tax year) or the physical presence test (being physically present in a foreign country for at least 330 full days during a 12-month period).

To claim the FHE, you need to file Form 2555 along with your annual tax return (Form 1040). This form requires you to detail your foreign housing expenses and verify your eligibility.

Benefits and limitations of the foreign housing exclusion

Benefits:

- Tax savings: By excluding eligible housing costs from your taxable income, the FHE can significantly lower your overall tax liability.

- Increased savings for high-cost areas: If you live in a high-cost area, you may be able to exclude more, leading to greater tax savings.

Limitations:

- Exclusion cap: The exclusion has a cap, which varies by location and cost of living. For 2024, the maximum exclusion is $37,950. Additionally, there is a floor of 16% of the Foreign Earned Income Exclusion (FEIE) limit, meaning only housing costs in excess of this amount can be excluded. If your housing expenses do not exceed this floor, there will be no benefit. This is a common scenario for nomads living in lower-cost regions such as Asia.

- Non-qualifying expenses: Certain expenses, such as luxury items, domestic help, and pay-per-use services like internet and cable TV, are not eligible for exclusion. Also the IRS did stop allowing foreign property taxes in 2017.

- Documentation: Housing costs are determined by location, so at a minimum, you must document how much was spent per country or city. Higher-cost locations like London have higher thresholds than places like Chiang Mai. You must maintain detailed records and receipts of your housing expenses to support your claim.

Foreign Bank Accounts Reporting (FBAR)

The FBAR (Foreign Bank Account Report) requirement mandates that U.S. citizens and residents report their foreign financial accounts to the Department of Treasury using FinCEN Form 114. This regulation helps prevent tax evasion through undisclosed offshore accounts.

Thresholds for reporting

You must file an FBAR if the aggregate value of all your foreign financial accounts exceeds $10,000 at any point during the calendar year. This includes bank accounts, brokerage accounts, mutual funds, and other foreign financial assets.

Consequences of non-compliance

Failure to comply with FBAR requirements can result in severe penalties. Non-willful violations may incur fines up to $10,000 per violation. Willful violations can lead to penalties of the greater of $100,000 or 50% of the account balance at the time of the violation, along with potential criminal charges.

FATCA compliance

The Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA) aims to prevent tax evasion by U.S. taxpayers holding financial assets abroad. It requires foreign financial institutions to report account information to the IRS, significantly impacting American nomads by increasing their reporting obligations.

Reporting requirements (Form 8938)

Under FATCA, U.S. taxpayers must file Form 8938 if their foreign financial assets exceed certain thresholds ($200,000 for single filers living abroad, $400,000 for married filing jointly). This form is filed with your annual tax return (Form 1040).

Penalties for non-compliance

Failure to comply with FATCA reporting requirements can result in substantial penalties. Non-filing can incur fines starting at $10,000, with additional penalties up to $50,000 for continued failure after IRS notification. Criminal penalties may also apply in cases of willful non-compliance.

Self-employment taxes

If you're self-employed as an American nomad, you are required to pay self-employment taxes, which cover Social Security and Medicare contributions. These taxes apply to your net earnings from self-employment and are mandatory regardless of where you live and work globally.

How to calculate and pay self-employment taxes (Schedule SE)

To calculate your self-employment taxes, you'll need to fill out Schedule SE and attach it to your annual tax return (Form 1040). The self-employment tax rate is 15.3%, which includes 12.4% for Social Security and 2.9% for Medicare.

- Social Security Tax: This rate applies to the first $160,200 of your net earnings for the 2023 tax year, increasing to $168,600 for the 2024 tax year.

- Medicare Tax: The 2.9% Medicare tax applies to all net earnings, with no income limit. Additionally, after $200,000 in earnings, an additional 0.9% Medicare surtax is applied.

Some countries have Totalization Agreements with the U.S. These agreements are designed to prevent double taxation of social security. If you live in a country with such an agreement and pay into that country's social security system, you may be exempt from paying U.S. Social Security taxes.

This can simplify your tax obligations and potentially reduce your overall tax burden. To claim this exemption, you typically need to file a statement with your tax return indicating your eligibility under the Totalization Agreement.

Business structures for nomads

- LLC (Limited Liability Company): An LLC provides limited liability protection to its owners and offers flexible management structures. It is a popular choice for small businesses due to its simplicity and tax flexibility. LLCs can be structured as single-member (owned by one person) or multi-member (owned by multiple people). The management can be member-managed or manager-managed.

- C-Corp (C Corporation): A C-Corp is a separate legal entity from its owners, offering strong liability protection. It can raise capital through the sale of stock but is subject to double taxation—once on corporate income and again on dividends paid to shareholders.

- S-Corp (S Corporation): An S-Corp combines the benefits of a corporation with the tax benefits of a partnership. It allows income to pass through to shareholders, avoiding double taxation. However, it has restrictions on the number and type of shareholders and requires compliance with strict regulations.

Benefits and drawbacks of each structure for self-employed nomads

LLC:

- Benefits: Flexible tax treatment, limited liability protection, straightforward setup, and management. LLCs can be taxed as a sole proprietorship, partnership, or corporation.

- Drawbacks: Potential self-employment taxes on all earnings, and administrative costs can vary by state. Annual fees and compliance requirements also vary depending on the state of incorporation.

C-Corp:

- Benefits: Strong liability protection, ability to raise capital through stock, perpetual existence, and potential for various tax deductions and credits.

- Drawbacks: Double taxation, complex setup and maintenance, and extensive regulatory requirements. Suitable for businesses seeking significant investment or planning to go public.

S-Corp:

- Benefits: Pass-through taxation avoids double taxation, potential savings on self-employment taxes, and limited liability protection. Dividends are not subject to self-employment tax.

- Drawbacks: Restrictions on the number and type of shareholders, stringent compliance requirements, and the necessity of paying reasonable salaries to owners. Suitable for businesses that meet specific IRS criteria and are primarily owned by U.S. citizens or residents.

When to switch from self-employment to an LLC, C-Corp, or S-Corp

- LLC: An LLC is useful once you need liability protection, such as if you have significant risk or personal assets, or if your clients prefer working with a more formal business entity. While sole proprietorships and LLCs are similar tax-wise, the LLC offers more credibility and protection. However, a drawback is that the Foreign Earned Income Exclusion (FEIE) is calculated on gross business income, with expenses deducted after the FEIE is applied, which can reduce the benefit of the FEIE for businesses with high expenses.

- C-Corp: C-Corps are typically chosen when you are looking to raise investor capital, go public, or if you're building a product that you ultimately want to sell. The double taxation aspect can be a downside, but the ability to raise significant capital and the perpetual existence of the corporation make it an attractive option for certain businesses.

- S-Corp: S-Corps usually start to make sense at a certain income level—between $60,000-$70,000 for those not taking the FEIE, and the FEIE max for those who do take it. S-Corps can provide tax savings on self-employment taxes, but they require careful management of reasonable compensation. In an S-Corp structure, only salary counts towards the FEIE, so maximizing salary to take advantage of the FEIE can reduce the employment tax savings that the S-Corp structure provides. This balance can be delicate and requires careful consideration.

Offshore structures for digital nomads

Setting up an offshore structure can offer substantial tax advantages for digital nomads, particularly by reducing or eliminating U.S. self-employment taxes. The two primary offshore setups include:

- Pure offshore setup: Establishes a foreign corporation (FC) in a tax-advantaged jurisdiction. Income and expenses flow through this corporation, and the owner pays themselves a salary from the FC, thereby avoiding U.S. self-employment taxes. When combined with the Foreign Earned Income Exclusion (FEIE) and Foreign Housing Exclusion (FHE), this can significantly reduce overall tax liability.

- Hybrid U.S./offshore setup: In this setup, a U.S. LLC is wholly owned by the offshore corporation. This allows the nomad to maintain a U.S. presence for banking or client reasons while still routing income through the foreign entity. Income can be passed through the LLC to the FC, where the owner then pays themselves, avoiding self-employment taxes. Proper management of this structure, including meticulous record-keeping and ensuring that the LLC is owned by the FC, is crucial to avoid IRS scrutiny.

Key considerations and compliance

While offshore structures offer significant tax benefits, they also come with compliance challenges. Key points include:

- GILTI Tax: The Global Intangible Low-Taxed Income (GILTI) tax applies to certain profits of foreign corporations and can range from 10% to 13.125%. This tax affects income from services provided by related parties outside the country of incorporation.

- Filing requirements: Offshore structures involve complex filing obligations, such as Form 5471 for reporting U.S. ownership in a foreign corporation and Form 5472 for LLCs that are at least 25% foreign-owned. Penalties for non-compliance can be severe, up to $25,000 for failing to file Form 5472.

Local and foreign taxes

When living abroad, it is essential to familiarize yourself with the local tax laws of your host country. Understanding the various taxes for digital nomads, including federal and state income taxes, corporate taxes, and self-employment taxes, is essential for managing your tax obligations effectively.

Each country has its own set of tax regulations that dictate your tax responsibilities. Key aspects to consider include income tax rates, taxable income definitions, deductions, and credits available to residents.

Consulting with a local tax advisor can help navigate these regulations effectively.

How to determine your local tax residency status

Determining your tax residency status is crucial as it impacts your tax obligations. Various triggers can determine tax residency, including:

- Physical presence: Spending more than 183 days in a country during a tax year often makes you a tax resident. However, some countries also consider cumulative days over multiple years.

- Permanent home: Having a permanent home available in the host country can establish tax residency.

- Center of economic interests: Factors such as employment, business ties, property ownership, and family location are considered to determine your primary place of economic activity.

- Domicile: Some countries consider your domicile, which is your permanent legal home, different from where you currently reside.

Countries like Australia use multiple tests (resides test, domicile test, and the 183-day test) to determine tax residency status. In contrast, countries like Ireland also consider ordinary residence, which applies if you have been a resident for three consecutive years and continues for three years after you cease to be a resident .

Common local taxes for expatriates

Expats may be subject to various local taxes, including:

- Income Tax: Tax on earned income, with rates and brackets varying by country.

- Social Security Contributions: Payments towards the host country's social security system, covering benefits such as healthcare and pensions.

- Value-Added Tax (VAT): A consumption tax applied to goods and services, impacting the cost of living.

- Property Taxes: Taxes on owned real estate, based on property value.

- Wealth Taxes: Taxes on the total value of personal assets, including savings and investments.

- Capital Gains Tax: Taxes on profits from the sale of assets like stocks, bonds, or real estate.

Steps to ensure compliance with local tax laws

- Research local tax laws: Understand the tax obligations in your host country, including income tax rates, filing requirements, and deadlines. Consulting a local tax advisor can provide tailored guidance.

- Register with local tax authorities: Ensure you are registered with the local tax authorities if required. This may involve obtaining a tax identification number.

- Maintain accurate records: Keep detailed records of your income, expenses, and any taxes paid. This includes contracts, receipts, bank statements, and any correspondence with tax authorities.

- File annual tax returns: Submit your tax returns on time, ensuring all income and deductions are accurately reported. Use the services of a local tax professional if necessary.

- Understand social security contributions: If applicable, register for and pay into the host country's social security system.

- Stay informed of changes: Tax laws can change frequently, so stay updated on any changes in local tax regulations that might affect your obligations.

Strategies for managing local and U.S. tax obligations simultaneously

- Utilize tax treaties: Leverage any tax treaties between the U.S. and your host country to minimize your tax burden. These treaties often provide benefits like reduced tax rates and protection against double taxation.

- Claim Foreign Tax Credits: Use Form 1116 to claim credits for taxes paid abroad, which can reduce your U.S. tax liability dollar-for-dollar.

- Exclude foreign earned income: File Form 2555 to exclude a portion of your foreign-earned income from U.S. taxation if you meet the eligibility criteria.

- Keep detailed records: Maintain thorough records of all income, expenses, and taxes paid in both the U.S. and your host country to support your tax filings.

- Consult tax professionals: Engage with tax professionals familiar with both U.S. and local tax laws to ensure compliance and optimize your tax strategy. They can provide advice on the best ways to file and reduce your overall tax burden.

- Stay organized and timely: Ensure timely filing of tax returns in both jurisdictions. Use tax software or professional services to keep track of deadlines and required documentation.

Bilateral tax agreements

Tax treaties, also known as bilateral tax agreements, are arrangements between two countries to resolve issues involving double taxation of income. The United States has tax treaties with over 60 countries to help prevent double taxation and tax evasion, promoting cross-border trade and investment.

These treaties typically cover income taxes, including taxes on income from personal services, pensions, dividends, interest, royalties, and other income sources.

Krystal Pino Leeds, Founder of Nomadtax

How to take advantage of bilateral tax agreements

To benefit from a tax treaty, you must:

- Identify applicable treaties: Determine if the U.S. has a tax treaty with your host country. The IRS provides a comprehensive list of U.S. tax treaties.

- Understand treaty provisions: Each treaty has specific provisions and benefits, which may include reduced tax rates or exemptions on certain types of income. Understanding these provisions can help optimize your tax situation.

- Claim treaty benefits: To claim benefits, you typically need to file the appropriate forms with your tax return. For instance, Form 8833 is used to disclose treaty-based positions. Additionally, you may need to provide documentation to the foreign tax authorities to benefit from reduced withholding rates on dividends, interest, and royalties.

- Consult a tax professional: Navigating tax treaties can be complex. Consulting a tax professional who understands both U.S. and foreign tax laws can ensure you fully utilize the benefits available under the treaty.

Examples of common tax treaty benefits

- Reduced withholding rates: Many treaties reduce or eliminate withholding taxes on dividends, interest, and royalties. For example, the U.S.-U.K. tax treaty reduces the withholding tax on dividends to 15% for portfolio investors.

- Exemption for certain types of income: Some treaties exempt specific types of income from taxation in the source country. For instance, the U.S.-Canada tax treaty allows certain pension payments to be taxed only in the country of residence.

- Relief from double taxation: Tax treaties often provide mechanisms for relief from double taxation, such as allowing taxpayers to credit taxes paid in one country against taxes due in another.

- Permanent establishment rules: Treaties define what constitutes a permanent establishment, which can affect whether business profits are taxable in the host country. This can prevent businesses from being taxed on their worldwide income by the host country if they do not have a substantial presence there.

Bona Fide Residence Test and Physical Presence Test

What is the Bona Fide Residence Test?

The Bona Fide Residence Test is a crucial requirement for U.S. citizens and green card holders aiming to qualify for the Foreign Earned Income Exclusion (FEIE).

This test mandates that you demonstrate bona fide residency in a foreign country for an entire calendar year. Essentially, you must establish a permanent home in the foreign country and be physically present there for at least 12 consecutive months.

To meet the Bona Fide Residence Test, you must:

- Be a U.S. citizen or green card holder.

- Have a permanent home in a foreign country.

- Be physically present in the foreign country for at least 12 months.

- Establish a tax home in the foreign country.

This test is more stringent than the Physical Presence Test, as it requires a deeper commitment to living in a foreign country, including establishing a permanent home and maintaining physical presence for an extended period.

What is a tax home?

A tax home is the location where your main place of business or work is situated. For U.S. citizens and green card holders, the tax home is typically the United States. However, for digital nomads who work remotely, the tax home may be in a foreign country.

To determine your tax home, consider the following factors:

- The location of your main place of business or work.

- The location of your permanent home.

- The location of your family and personal ties.

The concept of a tax home is vital for U.S. citizens and green card holders because it determines where you are subject to income taxes. If your tax home is in a foreign country, you may be eligible for various tax benefits, such as the Foreign Earned Income Exclusion (FEIE) and the Foreign Housing Exclusion.