A simple guide to New York residency laws

Understanding New York’s residency laws is important for income tax purposes because it determines how much you might owe in state taxes. Whether you live in New York full-time, part of the year, or even just spend occasional time there, the state has specific rules for classifying your residency status. Your residency classification affects whether you’re taxed on just the income you make in New York, or on everything you earn worldwide.

In this article, we’ll explain the different types of residency in New York—whether you’re considered a resident, non-resident, or part-year resident. We’ll also cover key terms like domicile and permanent place of abode, and how these factors impact your tax responsibilities.

Residency classifications

New York classifies individuals into three main categories for tax purposes: New York State resident, non-resident, and part-year resident. Each classification comes with different tax obligations, so it’s important to know where you fall. Let’s break down what each term means.

You are considered a New York State resident if you meet one of two criteria:

- Domicile: New York is your permanent home. This means it’s the place where you intend to return whenever you’re away, and where your life is centered. You can only have one domicile at a time, so if New York is where your primary home is, the state considers you a resident for tax purposes.

- Statutory resident: You’re not domiciled in New York, but you (1) maintain a permanent place of abode (PPA) in New York for substantially all of the year (for tax years 2022+, Audit applies >10 months) and (2) spend more than 183 days in New York in that tax year. Any part of a day counts.

As a resident, New York taxes you on your worldwide income, meaning everything you earn, no matter where it comes from, is subject to New York state taxes.

Non-resident

A non-resident is someone who:

- Does not have a domicile in New York, and

- Does not maintain a permanent place of abode in New York for the majority of the tax year.

Non-residents are only taxed on new york source income, like wages earned while working in the state or income from New York-based investments or property.

Domicile

Your New York state domicile is your true, permanent home. It’s the place you always intend to return to after being away. Even if you spend a lot of time outside your home, your domicile is where you feel most connected and where your life is centered.

Changing your domicile: You can only have one domicile at a time. To change your domicile, you need to show that you’ve left your old home and set up a new permanent home in a different state. This involves more than just moving physically—it requires proving that you no longer intend to return to your old home. Things like selling your old house, changing your driver’s license, and registering to vote in a new state can help show that you’ve made a real change.

Permanent place of abode

A permanent place of abode is a residence that’s suitable for year-round living. This could be a house or apartment, and it doesn’t matter whether you own or rent it. What matters is that it’s a home that you can live in all year, not just a temporary or seasonal place like a vacation home.

To count as a permanent place of abode for tax purposes, you need to maintain the home for most of the year (more than 10 months) and use it as your residence. If you maintain such a home in New York and spend 184 days or more in the state, you may be considered a statutory resident, even if your domicile is elsewhere.

These definitions are crucial for determining whether New York will tax you as a resident or a non-resident. Your domicile reflects where your life is based, and your permanent place of abode can impact your tax status even if you don’t consider New York your main home.

Statutory residency rules

Even if New York isn’t your permanent home (domicile), the state can still consider you a statutory resident based on two main criteria for New York State residency. These rules are especially important for individuals who spend a significant amount of time in New York but maintain their primary home elsewhere.

Maintaining a permanent place of abode

You can be classified as a statutory resident if you maintain a permanent place of abode in New York for more than 10 months of the year. This means having a residence, like a house or apartment, that is suitable for year-round living. You don’t necessarily have to own the property; it could be rented or leased.

The key here is that the residence must be available for your personal use throughout the year. Temporary stays or vacation homes typically do not count unless you are using them as a primary residence for substantial parts of the year.

Spending 183 days or more in New York

In addition to maintaining a permanent place of abode, you also need to be physically present in New York for more than 183 days during the tax year to be classified as a statutory resident. Here’s an important detail: any part of a day you spend in New York counts as a full day for tax purposes. So, even if you’re just in New York for a few hours, it will be added to your total days in the state.

This rule is important for individuals who travel frequently between states or spend extended time in New York for work or personal reasons. If you exceed the 183-day limit while maintaining a permanent place of abode, New York may tax you as if you are a full-time resident.

Impact of New York state residency

If you meet both criteria—maintaining a permanent place of abode and spending 183 days or more in New York—you will be classified as a statutory resident. This means New York will tax you on your worldwide income, just like a full-time resident, even if your official domicile is in another state.

Tax implications of residency

Your residency status in New York—whether you’re a resident, non-resident, or part-year resident—directly impacts how much state tax you owe and on what types of income. Additionally, New York City residency impacts your tax liabilities, as city residents are subject to New York City personal income tax. Understanding how New York taxes each classification is essential to avoid surprises during tax season.

Residents

If you are classified as a resident of New York, the state taxes you on your worldwide income. This means that everything you earn, no matter where it’s from, is subject to New York state taxes. Whether you have investments abroad, work income in other states, or rental properties in other countries, you’ll need to report and pay taxes on all of it to New York.

Key point: As a resident, you cannot escape New York taxes by earning income outside the state. All income is subject to New York’s tax laws, and you must file a full-year resident tax return.

Non-residents

If you’re classified as a non-resident, you only owe taxes on income sourced from New York. This includes income from:

- Wages earned in New York: If you physically work in New York, even if you live in another state, the wages earned are taxed by New York.

- Rental income from New York properties: If you rent out property located in New York, the income from those rentals is subject to New York taxes.

- Business income: If you own or operate a business in New York, the income earned in-state will be taxed.

As a non-resident, you do not have to pay New York taxes on income earned from other states or countries, but you will need to file a non-resident tax return to report your New York-based income.

Part-year residents

Part-year residents are taxed as residents for the portion of the year when they lived in New York, and as non-residents for the time when they lived outside the state. Here’s how it works:

- For the time you were a resident: You will pay taxes on your worldwide income during the months you were living in New York.

- For the time you were a non-resident: You will only pay taxes on income sourced from New York during this period.

- You’ll file a part-year resident return (Form IT-203) with New York, reporting the income earned both while living in the state and while living elsewhere.

Avoiding double taxation

If you live in multiple states or earn income in different locations, you might worry about being taxed twice—once by New York and once by another state. Fortunately, New York offers tax credits to avoid double taxation.

If you’ve paid income taxes to another state on the same income that’s also taxable by New York, you can often claim a credit to offset your New York tax liability. These credits are designed to reduce the risk of being taxed twice on the same income, subject to New York’s specific rules and limitations.

Resident credit for foreign taxes (Canada-only)

New York’s resident foreign tax credit is limited: residents may claim a credit for Canadian provincial income taxes using Form IT-112-C. NY generally does not allow a resident credit for taxes paid to other countries. Bring documentation and expect add-backs if the same Canadian tax was claimed later on your federal Form 1116.

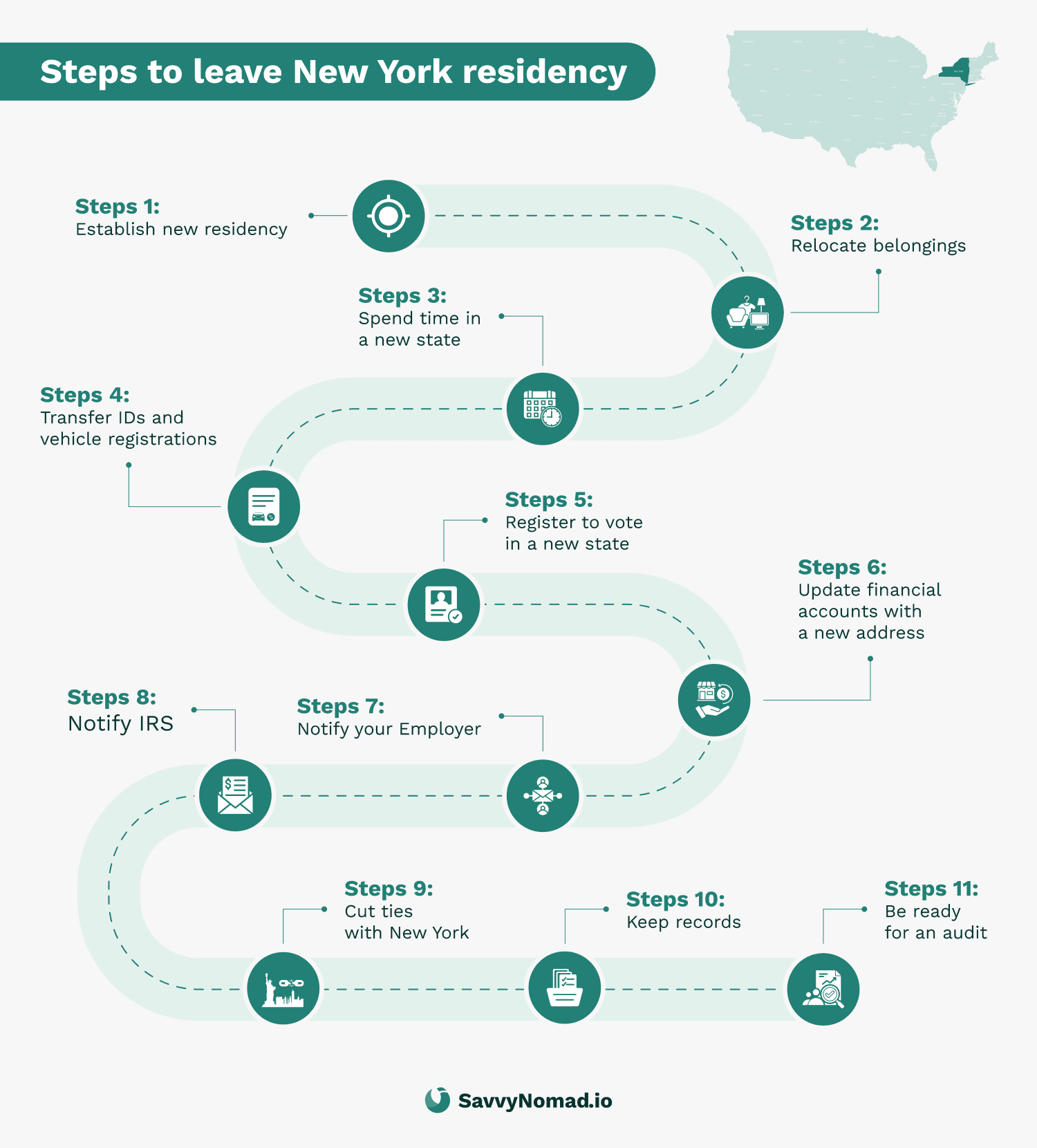

How to leave New York residency?

To officially terminate your New York residency and establish a new domicile in another state, it’s essential to take a series of deliberate steps.

These actions can help you support your position that you’ve left New York residency and established domicile elsewhere, and may reduce the risk of New York continuing to treat you as a resident for tax purposes.

You’ll still owe tax on New York-source income, and New York will apply its own rules when reviewing your situation.

Here’s a step-by-step guide to help you through the process.

1) Establish new residency

The first step in terminating your New York residency is to secure a residential address in your new state. For many people, that means buying or leasing a home; for full-time travelers, a domicile or residential-address service (such as SavvyNomad) can provide a bona fide residential street address and help you organize documentation.

The address and paperwork are part of the bigger picture, but they don’t, by themselves, prove a permanent move or guarantee how any state will treat you.

For example, some states like Florida offer property-tax benefits (such as the homestead exemption) that can support your intent to establish residency when you actually live there and qualify under their rules. Filing a Declaration of Domicile where available is another key step, as it formalizes your intent to make the new state your permanent home.

Acceptance always depends on each state agency, bank, or third party’s policies, and the address is not for business registration or public listings and does not, on its own, guarantee any tax outcome.

2) Relocate your belongings

Move your personal and valuable possessions out of New York to your new home to help demonstrate that you no longer treat New York as your primary residence. Keep detailed records, including receipts for moving services or storage facilities, as these will be important evidence of your relocation if New York reviews your case.

Remember, New York may scrutinize your move, so having documented evidence that you’ve moved your belongings out of the state will support your claim of terminating residency.

3) Spend time in your new state

The more time you spend in your new state, the easier it will be to show that you’ve genuinely moved. While some people may only visit long enough to get a driver’s license, it’s best to spend as much time as possible in your new state to solidify your status.

New York can challenge your claim if you regularly return to the state, so prioritize time spent in your new state to demonstrate that you’ve made it your home.

4) Transfer IDs and registrations

Immediately update your driver’s license and vehicle registration to your new state. New York views these as significant indicators of residency, and keeping your New York driver’s license can imply that you still consider it home.

Make sure to complete this step as soon as possible after relocating to show that you’ve committed to your new state.

5) Register to vote

Register to vote in your new state (if you’re eligible), and cancel your New York voter registration. Voter registration is a strong supporting indicator of residency, and participating in elections in your new state further supports your intent to make it your permanent home, but it’s just one factor among many that states consider.

6) Integrate into the community

Engaging in local activities and building relationships in your new state helps reinforce your commitment to living there. Join local organizations, find professionals like doctors or dentists, and become involved in the community.

This integration is more than just social—it serves as proof that you’ve fully transitioned your life to your new state.

7) Update all documents

Make sure that your identification, medical records, insurance policies, and financial documents reflect your new address. This includes updating your address with banks, credit cards, and insurance companies.

By consistently using your new state address on all official documents, you reinforce your claim that you’re no longer a New York resident.

8) Notify your employer

Inform your employer of your move and work with them so that your payroll reflects your new state residency. You should also file Form 8822 with the IRS to notify them of your address change. This step is important for both federal and state tax records.

Make sure that all other personal and professional entities (like accountants or financial advisors) are also informed of your relocation.

9) Notify the IRS

In addition to notifying your employer, formally update your address with the IRS by filing Form 8822. This is an important step in documenting your move for tax purposes and helps avoid confusion during tax filing.

Extend this notification to any other financial institutions or government agencies that require an updated address.

10) Keep records

Document every step of your relocation carefully. Keep receipts, contracts, utility bills, and legal documents that show you’ve moved your residence, established domicile in a new state, and severed ties with New York.

11) Acknowledge key factors

Make sure you feel confident about where you stand on these factors. For instance, if you still own a home in New York, ensure it’s rented out or treated as a secondary property, not your primary residence.

12) Anticipate an audit

To be audit-ready, keep thorough documentation of your move, including records of your new home, financial activity in your new state, and evidence that you’ve severed ties with New York.

Following these steps methodically can help you build a strong factual record that you’ve terminated your New York residency and established yourself in a new state, and may reduce the risk of New York pursuing resident-level taxes after you’ve moved.

No specific outcome is guaranteed, and New York will still apply its own residency rules and audit procedures to your facts.

Key characteristics of a permanent place of abode

A key element in New York’s residency rules is whether you maintain a permanent place of abode in the state. This plays a significant role in determining your tax obligations, especially if you spend considerable time in New York but claim residency elsewhere. Here’s what you need to know about what qualifies as a permanent place of abode.

Must be suitable for year-round living

To be considered a permanent place of abode, the residence must be suitable for year-round use. This means it should have the basic necessities for living, such as:

- Sleeping facilities (like a bedroom)

- Cooking capabilities (a functional kitchen)

- Bathing facilities (a bathroom)

The home doesn’t need to be a luxurious or large property, but it must be more than just a vacation home or temporary stay. Homes that are only suitable for seasonal use (like a summer cabin) typically do not count unless they are used significantly during the year.

Maintaining the residence

Maintaining a residence means that you have control over the property, whether you own or rent it, and you can access and use it at any time. You don’t have to be physically present all the time, but the property should be available for your personal use throughout the year.

Example: If you own an apartment in New York and keep it for personal use, even if you spend much of the year elsewhere, the state could classify it as your permanent place of abode.

Residential interest

New York courts have emphasized the importance of having a residential interest in the property. This means the dwelling isn’t just for occasional or recreational use, but serves as a place where you could live if needed. Simply owning a property in New York is not enough—there must be a clear, ongoing relationship with the home that reflects a residential purpose.

Example: A vacation home that you visit once or twice a year likely won’t qualify as a permanent place of abode. However, if you frequently use the home for extended stays, it may be considered your primary residence for tax purposes.

Examples of what qualifies and what doesn’t

- Qualifies: An apartment you rent year-round in New York that you regularly use for business or personal reasons.

- Doesn’t qualify: A seasonal vacation home that’s only used a few weeks in the summer.

Legal precedents and interpretations

Over the years, New York courts have ruled on several key cases that clarify what qualifies as a permanent place of abode and other aspects of residency status. Understanding these legal precedents can help you avoid missteps when determining your own residency and tax obligations. Let’s look at a few important cases.

Matter of Evans v. Tax Appeals Tribunal

In this case, the court emphasized that both the physical characteristics of the dwelling and the taxpayer’s relationship to it are critical in determining whether a property qualifies as a permanent place of abode. Simply having access to a home isn’t enough—it’s about how you use it and whether it’s maintained for personal, year-round living.

Matter of Barker

In this case, the court ruled that even if a vacation home is primarily used for leisure, if it’s suitable for year-round living and is maintained by the taxpayer, it can still qualify as a permanent place of abode. Barker had a vacation property that met the criteria for year-round use, and because he maintained the home, the court found it to be a permanent place of abode.

Matter of Obus

Conversely, in the Obus case, the court found that even though the taxpayer had access to a New York vacation home, it did not qualify as a permanent place of abode because there was no evidence that the home was used in a way that indicated a residential interest. The property was used very occasionally and didn’t meet the criteria for ongoing, year-round residency.

Practical implications

These legal cases demonstrate how carefully New York courts analyze both the nature of a dwelling and the taxpayer’s relationship to it. Even if you don’t live in New York full-time, maintaining a residence that qualifies as a permanent place of abode could trigger statutory residency and its associated tax obligations.

Retaining New York domicile while living abroad

You might think that moving abroad automatically terminates your New York residency, but that’s not necessarily the case. If you maintain your domicile in New York, the state could still classify you as a resident for tax purposes.

If you maintain a New York City residency, you may still be subject to New York City personal income tax even while living abroad.

Temporary nonresident safe harbors (30-Day & 548-Day)

If you remain domiciled in New York but are abroad, two narrow safe harbors can treat you as a temporary nonresident if you meet every condition and document it:

- 30-Day Rule (calendar-year): (1) No PPA in NY at any time during the year; (2) PPA outside NY for the entire year; (3) ≤30 NY days in that year (any part of a day counts).

- 548-Day foreign-assignment Rule: In 548 consecutive days, (1) you’re in foreign countries ≥450 days; (2) you, your spouse (unless legally separated), and your minor children are in New York ≤90 days in that span; and (3) in the short periods at the start/end of that 548-day window, your NY days do not exceed the pro-rated share of 90/548.These harbors do not change domicile; they confer temporary nonresident status only for the qualifying periods and are documentation-heavy.

What triggers New York residency even when abroad?

- If you continue to have significant ties to New York, such as owning property, maintaining financial accounts, or having family living in the state, New York may consider you a resident, even if you live most of the year abroad.

- Domicile is about intent. If New York is still the place where you intend to return after living abroad, you are likely still considered domiciled in New York.

How does New York track expats?

- New York can look at various indicators of residency, such as home ownership, travel records, where your business or family ties are, and how often you return to New York.

- Even if you spend most of your time abroad, keeping strong ties to New York could still classify you as a resident.

Am I still a New York resident if I live abroad?

If New York is still your domicile and you haven’t taken steps to officially change it, you will be considered a resident, subject to taxation on your worldwide income.

Taxation for domiciled expats

Living abroad doesn’t necessarily exempt you from New York taxes if your domicile is still in the state.

Worldwide income reporting obligations

New York residents are taxed on their worldwide income, meaning that even if you’re earning income abroad, you’ll need to report and pay taxes on it in New York. This includes wages, investments, and business income from any country.

How does the 183-day rule impact expats?

Even if you’re not domiciled in New York, you could still be classified as a statutory resident if you maintain a permanent place of abode in the state and spend more than 183 days there in a tax year. Any part of a day counts toward this total, so frequent or long visits to New York could affect your tax status.